Once upon a time there was a Spanish chaplain …

Capellanus quidam hyspanus … Which seems a good place to remember a trip to Spain about a month ago. I spent a week at the Biblioteca Nacional de España, looking at thirteenth-century Spanish manuscripts, most of them dated, no less! Here I am, trying to apply to a manuscript at Columbia —also Spanish, also thirteenth century— the lessons learned there. The trick is to distinguish these from Italian manuscripts of the same date. Take that line “Capellanus quidam hyspanus”; the decorative letter C is enclosed in a completely filled-in frame, more rectangular than square; that looks Spanish to me. The dotted y, oh yes, that’s Spanish. And the h here and in “adhibuit” in the top line: a spike at the top of the bowl, whose right arm hangs just a tad below the line. More easily noticeable is the shape of the tironian seven with its completely flat nose sticking out at a right angle from the supporting minim: Spanish? well, yes, but in the south of France, too.

Which seems a good place to remember a trip to Spain about a month ago. I spent a week at the Biblioteca Nacional de España, looking at thirteenth-century Spanish manuscripts, most of them dated, no less! Here I am, trying to apply to a manuscript at Columbia —also Spanish, also thirteenth century— the lessons learned there. The trick is to distinguish these from Italian manuscripts of the same date. Take that line “Capellanus quidam hyspanus”; the decorative letter C is enclosed in a completely filled-in frame, more rectangular than square; that looks Spanish to me. The dotted y, oh yes, that’s Spanish. And the h here and in “adhibuit” in the top line: a spike at the top of the bowl, whose right arm hangs just a tad below the line. More easily noticeable is the shape of the tironian seven with its completely flat nose sticking out at a right angle from the supporting minim: Spanish? well, yes, but in the south of France, too.

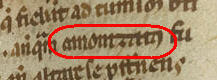

Odd, 3-shaped Spanish z. The trouble is that a z doesn’t come up very often, so it’s not a great letter to use as part of your criteria. Surprisingly, I found three on one page (f. 45): canonizatum; amonizatus [sic, one “m”]; intronizatum.

A bunch of interesting letter forms here: two shapes for the letter a, one of which is entirely teardrop (in a blue circle), the second, though, has a tiny little line as if to close the top bowl, but with no courage at all (so, appropriately, it is designated with a yellow circle). Violet circles help the eye find the letter d which always occurs in the present uncial form (never the straight half-uncial d). Teal blue-green circles show the slippery s at the end of a word (but the straight s does put in an occasional appearance).

A bunch of interesting letter forms here: two shapes for the letter a, one of which is entirely teardrop (in a blue circle), the second, though, has a tiny little line as if to close the top bowl, but with no courage at all (so, appropriately, it is designated with a yellow circle). Violet circles help the eye find the letter d which always occurs in the present uncial form (never the straight half-uncial d). Teal blue-green circles show the slippery s at the end of a word (but the straight s does put in an occasional appearance).

The best ever marker, though, for the non-Italian-ness of this manuscript (that being my main risk of confusion, I’d say), is the northern European qui abbreviation mark! Can we blame Cluny for this intrusion into Spain? Anyway, enclosed in red frames here, are the words “quidam” and “quid.” Perfect. No Italian would write them like this, no way.

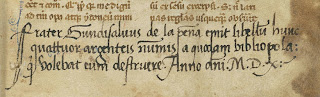

Columbia’s manuscript —it’s Western MS 68— almost didn’t make it to today’s world. It was saved from destruction by a bookseller for the price of four silver coins by Brother Gonzalez de la Peña in 1510, as he tells us on the front page: “Frater Gundisalvus de la peña emit libellum hunc quattuor argenteis nummis a quodam bibliopola qui [qui abbreviation that looks one whole lot more Italian than Spanish!] volebat eum destruere Anno domini M. D. X.”

Columbia’s manuscript —it’s Western MS 68— almost didn’t make it to today’s world. It was saved from destruction by a bookseller for the price of four silver coins by Brother Gonzalez de la Peña in 1510, as he tells us on the front page: “Frater Gundisalvus de la peña emit libellum hunc quattuor argenteis nummis a quodam bibliopola qui [qui abbreviation that looks one whole lot more Italian than Spanish!] volebat eum destruere Anno domini M. D. X.”

To close, I’ll repeat a kindly colophon seen in a manuscript in Spain (Madrid, Biblioteca Nacional de España, MS 871, f. 142v):

“Sit pax scribenti, Sit vita salusque legenti.”

“May there be peace for the scribe, May there be life and health for the reader.”