The Dunning School of . . . Baseball?

(Written by Nick Osborne)

William Archibald Dunning was one of the most influential US historians of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Even as he wrote such works as Essays on the Civil War and Reconstruction (1898), Dunning trained numerous other scholars from his perch as the Francis Lieber Professor of History and Political Philosophy at Columbia. His influence was so great that his and his students’ writings on the Civil War and Reconstruction eventually became known as the “Dunning School.” Though now widely-discredited for their frequently explicit racism and overt hostility to Northern politicians, Dunning School historians dominated historiography about the mid-nineteenth century US for much of the first half of the twentieth century.

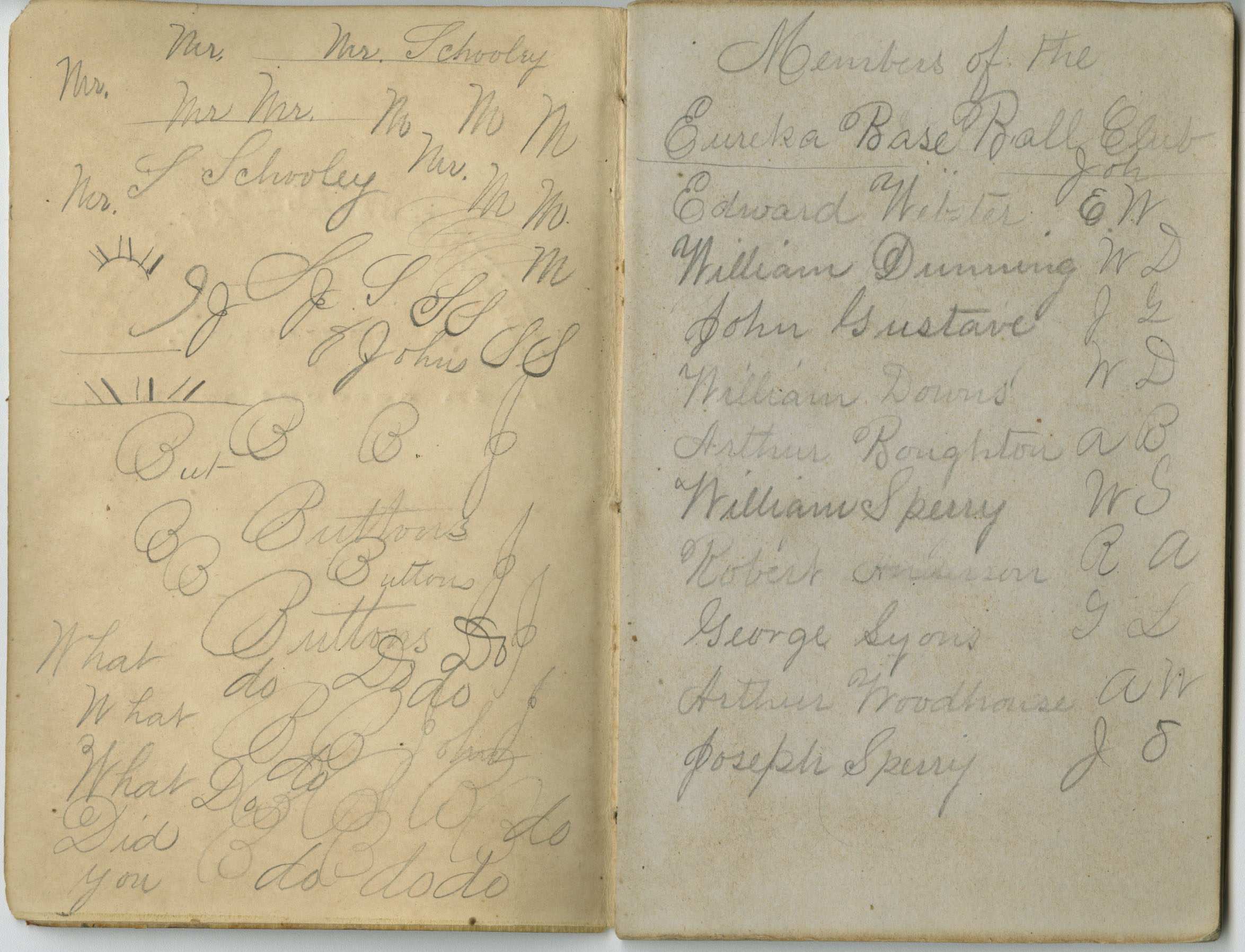

That brief overview describes the background knowledge I brought with me as I ventured into the William A. Dunning Papers at RBML. Specifically in search of Dunning’s diaries for a project I’m working on that involves identifying diaries written by Americans and held throughout all RBML collections, I was intrigued by the possibility of gaining insight into the personal views of such an infamous past member of my profession or an insider’s look at Columbia at the turn of the twentieth century. What I didn’t expect to find was a glimpse of a thirteen-year-old boy growing up in Plainfield, New Jersey, practicing his penmanship and playing baseball.

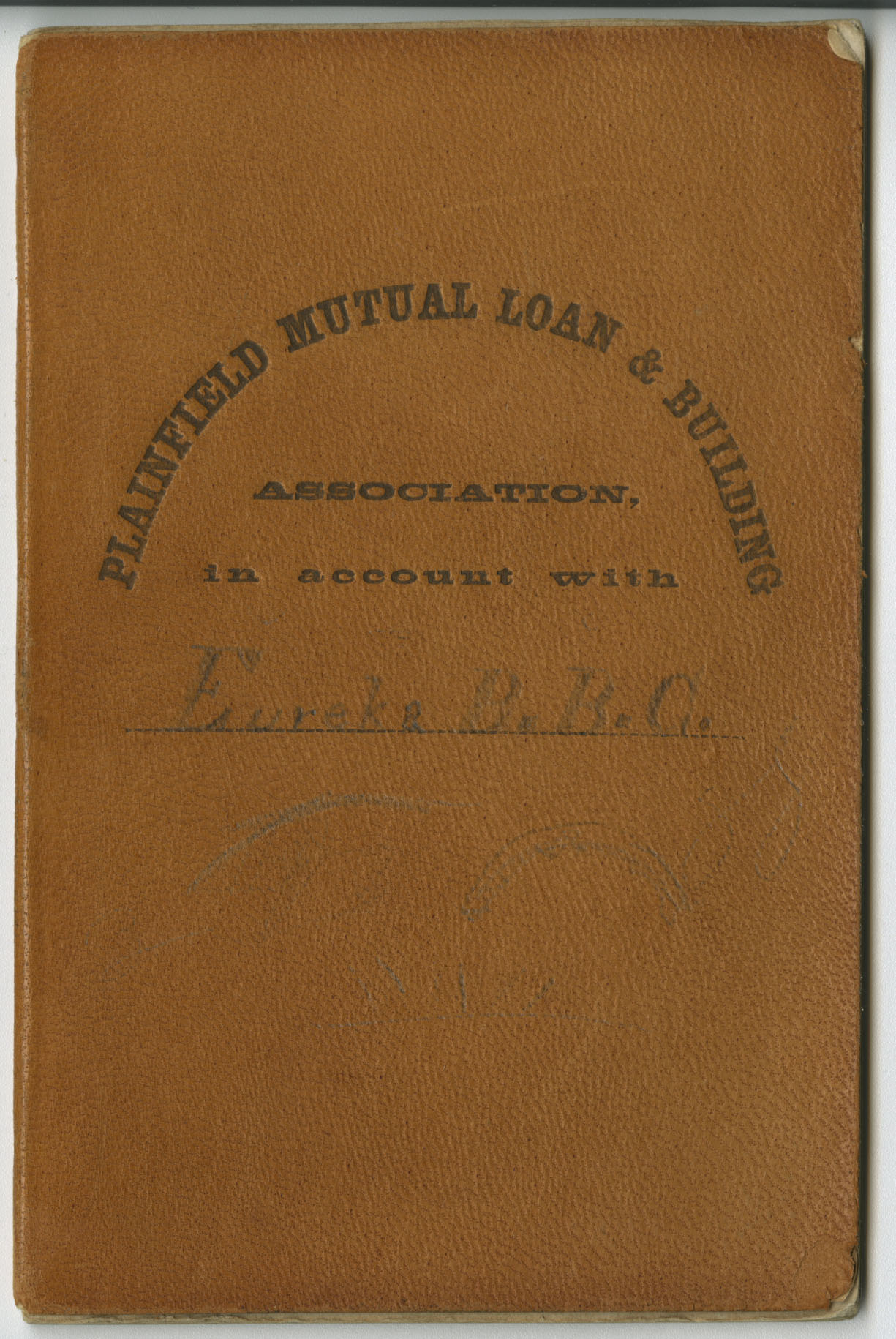

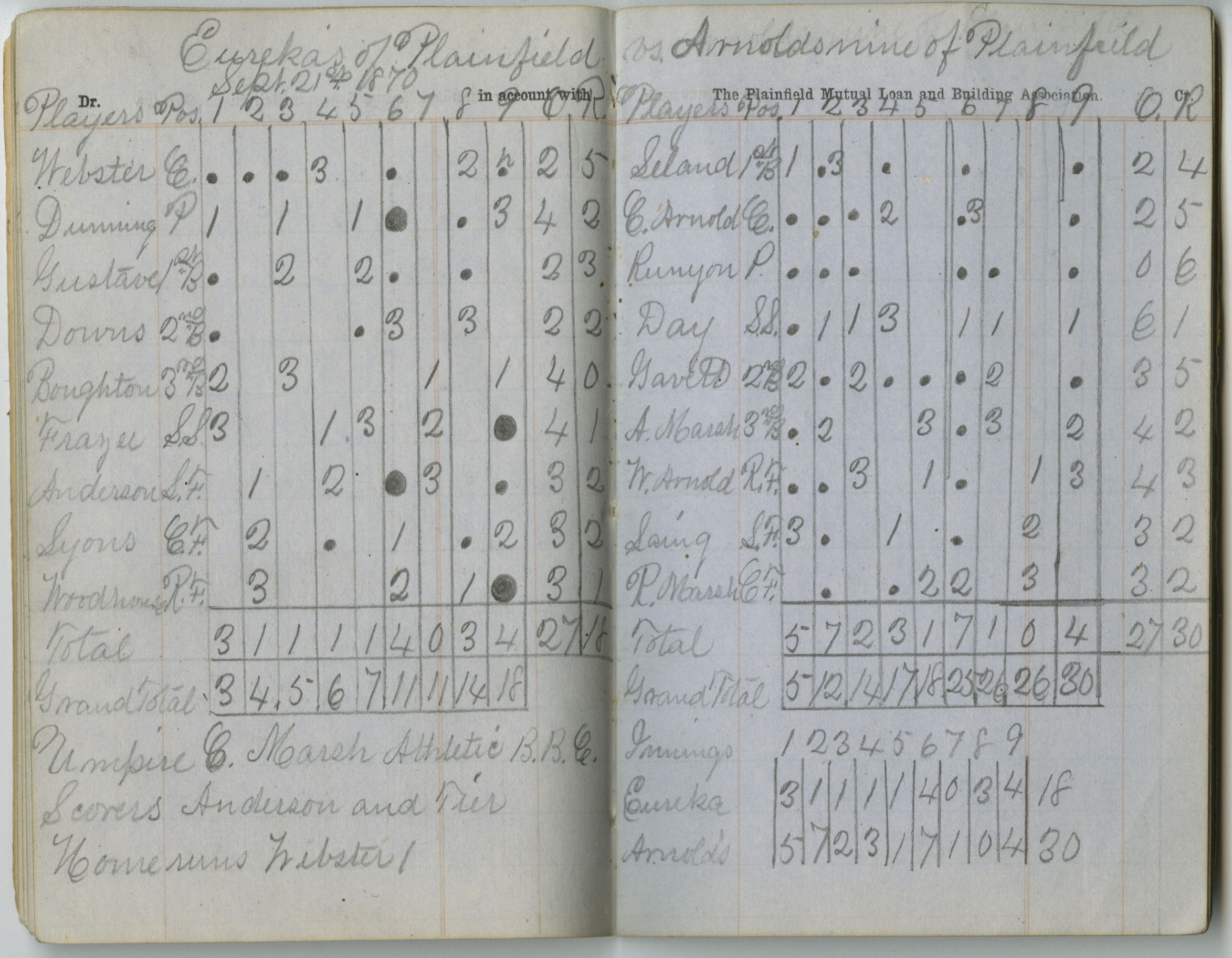

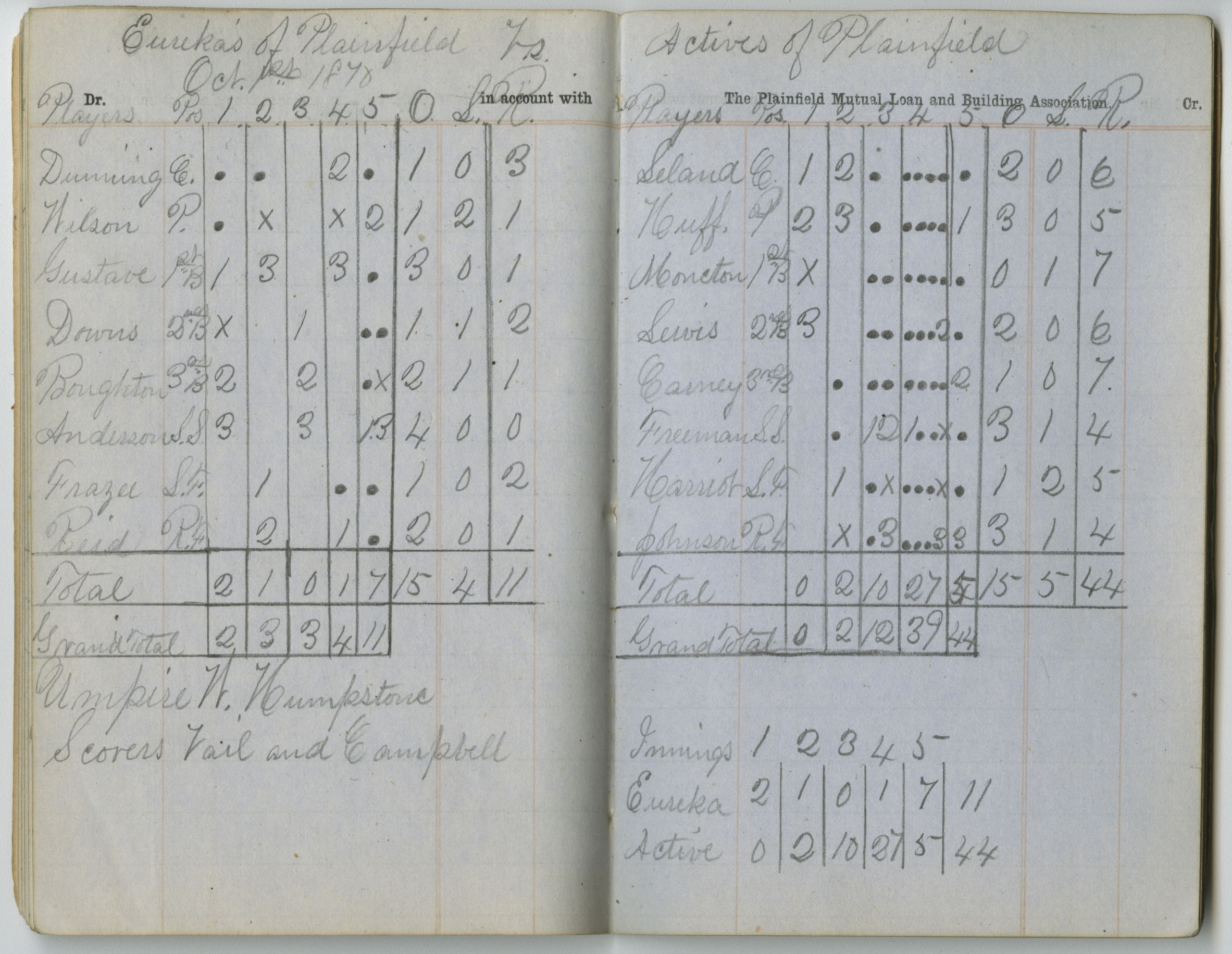

Yet that is what the following item I discovered shows. Mixed in with the diaries in the collection, it was originally a bankbook issued to record shareholding and other transactions with the Plainfield Mutual Loan & Building Association.

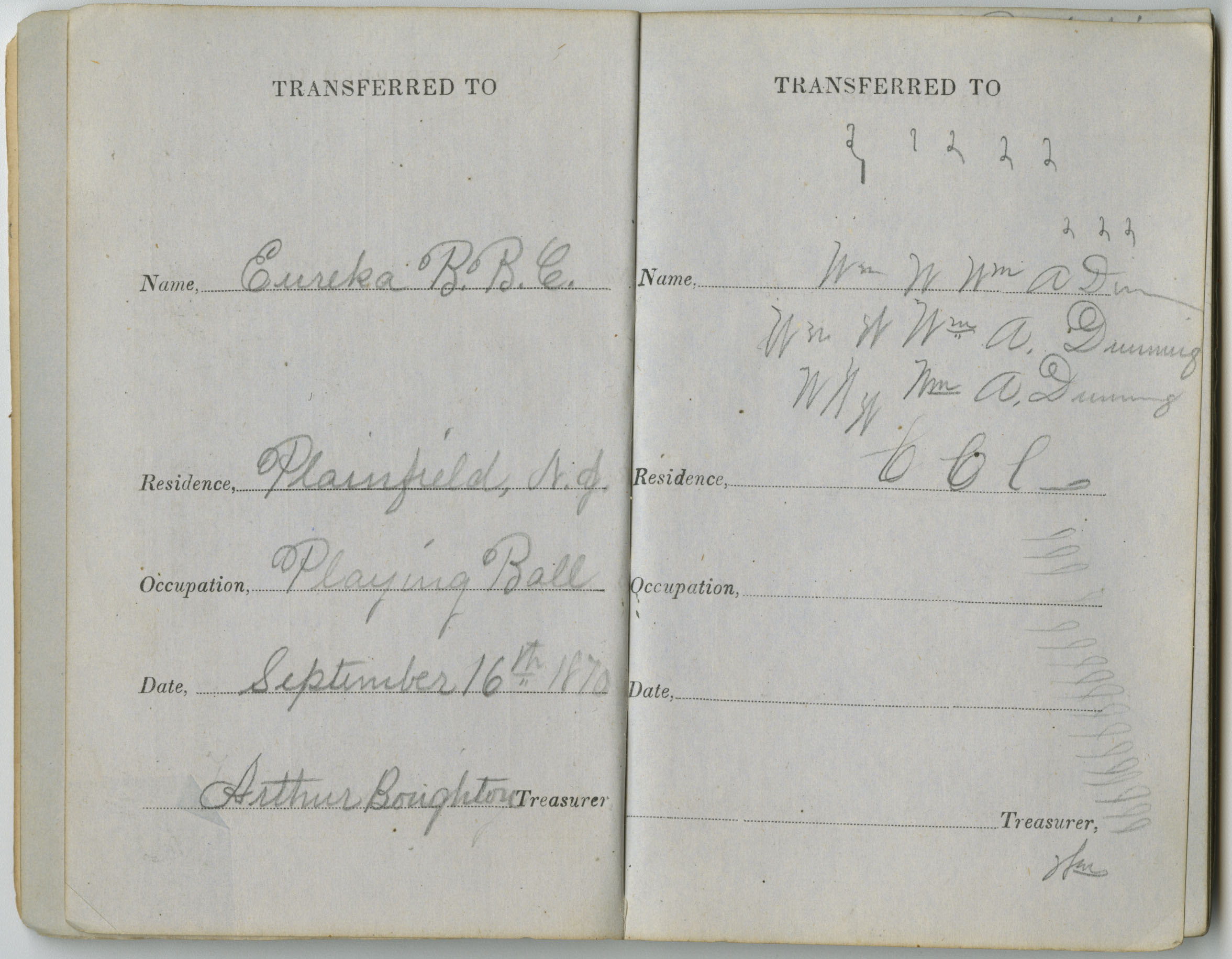

But sometime in 1870, Dunning repurposed it for a far more thrilling purpose (at least from the perspective of an adolescent child): to keep score for his “Eureka Base Ball Club.”

But sometime in 1870, Dunning repurposed it for a far more thrilling purpose (at least from the perspective of an adolescent child): to keep score for his “Eureka Base Ball Club.”

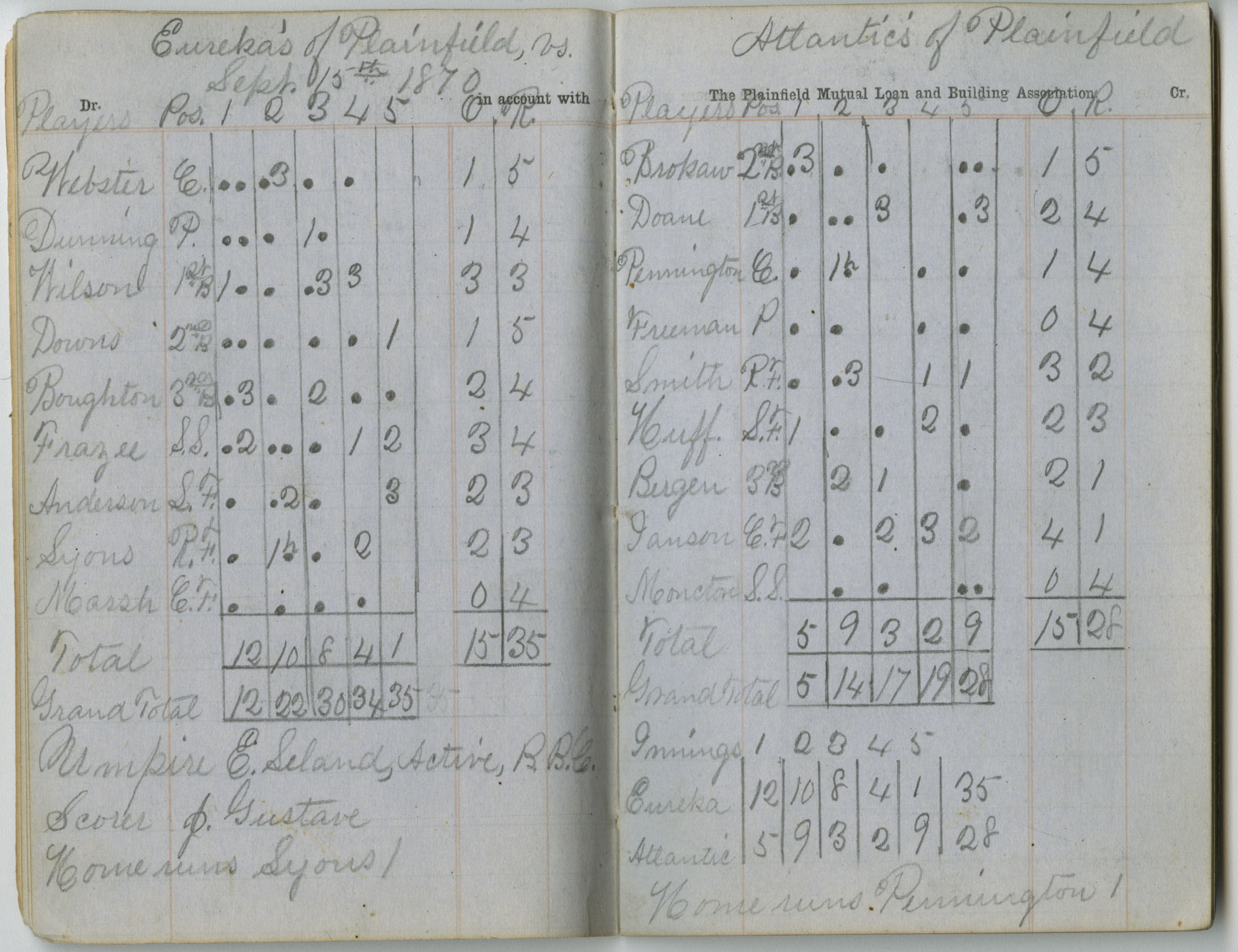

Apart from showing Dunning’s youthful sense of humor (note that he filled out the “occupation” of the team as “Playing Ball”), this book also provides a brief glimpse at America’s national pastime just as it was starting to take on its modern form. (The first baseball game played with a team composed entirely of professional players, the Cincinnati Red Stockings, took place just a year earlier in 1869.) To read these scorecards, note that each column corresponds to an inning (the first and third games were only five innings long; the second was a full nine), dots signify “runs scored,” and the numbers in each inning’s column correspond to who made the first, second, and third outs of the inning.

From a baseball perspective, these scorecards suggest a fairly loose game was being played in Plainfield in 1870–the final scores were 35-28, 30-18, and 44-11. From a personal perspective, they show that long before Dunning became a lion of the historian’s field, he pitched and caught against the “Atlantic’s,” the “Arnolds nine,” and the Actives”. That might not add much to our understanding of the Civil War and Reconstruction, but it is a pleasant reminder that even those historical figures who went on to achieve fame, then infamy, sometimes started out as thirteen-year-old boys playing ball in Plainfield, NJ.

[by Nick Osborne]