On today’s date — April 30 — in 1968, the campus takeover by thousands of Columbia and Barnard community members ended in violence, as police physically removed students, and others, from university buildings that they had occupied during the previous week. On the same date, seven years later, Saigon, the capital of South Vietnam, fell to North Vietnamese forces — finally ending the decades-long conflict in the region.

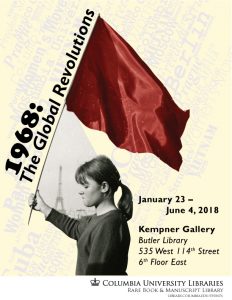

Both of these momentous historical events are documented in “1968: The Global Revolutions,” a major exhibition that originally appeared in the spring of 2018, in the RBML’s Kempner Gallery, and is now fully digitized and available for online viewing.

From Hanoi to Harlem, Czechoslovakia to China, Memphis to Paris, the yearlong crises of 1968 rocked world

communities with an epoch-making series of political explosions. In late April 1968, “The Revolution” came to campus at Columbia University. “1968: The Global Revolutions” uses Columbia archival documents to trace the connections between those worldwide upheavals, linking them together to demonstrate how many local and national movements looked to peers and comrades in other countries, campuses, and communities.

Highlights from the exhibition:

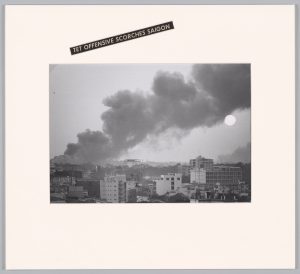

Photographs of the Tet Offensive

“Tet Offensive Scorches Saigon,” 1968

Pulitzer Prizes Committee Records

The Tet Offensive, launched in January 1968 by forces from North Vietnam and the National Liberation Front, targeted more than 100 towns and cities throughout South Vietnam. In the most dramatic hours of the attack, Vietnamese guerrilla fighters occupied the grounds of the U.S. Embassy in Saigon, the symbolic center of the American war effort. Though Communist troops suffered catastrophic losses in these efforts, their ability to penetrate into the heart of South Vietnamese territory suggested to government officials, and to the broader American public, that – despite the presence of hundreds of thousands of troops, and the full, deadly arsenal of the American military – the United States was engaged in a war it could not win.

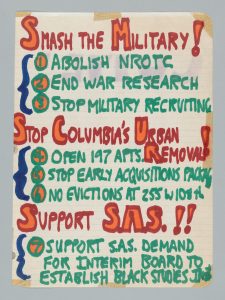

Original Ephemera from the 1968 Columbia Student Protests

Hand-Colored Flyer, 1968

University Protest and Activism Collection

Columbia University’s chapter of Students for a Democratic Society had been organizing continuous campus protests during the fall of 1967. The spring 1968 semester was marked by teach-ins, lectures, screenings of anti-war films (such as Alain Resnais’s Hiroshima Mon Amour), and frequent rallies. SDS and the Student Afro-American Society worked to demonstrate and raise awareness about the university’s collaboration in military research, as well as its role as a rapacious landlord in Harlem. Among the various issues of concern, none generated more anger than Columbia’s plans to encroach on historic Morningside Park by building a university athletic complex that would be off-limits to community members – an act condemned by opponents as an instance of “Gym Crow”. In March 1968, several SDS members were placed on academic probation for their protest activities, building polarization, and catalyzing the conflict that was to come.

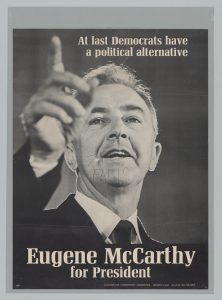

The 1968 Presidential Election

Eugene McCarthy’s campaign for president in 1968 appealed to youth voters and the peace movement by promising to bring a swift end to the Vietnam War. His strong showing in early primaries demonstrated President Johnson’s weakness, and inspired Robert F. Kennedy to enter the race. Johnson then announced he would not seek re-election and Kennedy was assassinated. McCarthy went on to win the popular vote for the nomination, leaving him and his eventual opponent – Vice President Hubert Humphrey – to fight for delegates at the Democratic Convention. Though McCarthy ran a popular campaign, he never quite succeeded in converting the most militant of student activists, who by 1968 had been disillusioned by all forms of conventional party politics. The Hitler mustache and scrawled word “Fascist” on this poster suggest the view radical protesters held of even the most progressive major party candidates.