Note: We always welcome corrections and other feedback on our finding aids. Please contact us at rbml@library.columbia.edu if you notice anything in a finding aid, including a subject heading, that needs attention.

A colleague recently asked an excellent question: why do the subject headings in our finding aids frequently use outdated terminology? It seems likely that other library users have wondered the same thing. As such, I think it deserves an explanation in writing.

The subject headings we—and the vast majority of American libraries—use are not locally determined. They are controlled by the Library of Congress. Proposals to add or revise Library of Congress Subject Headings (LCSH) go through a lengthy review process. Required supporting documentation for LCSH proposals can include definitions of the term and its variations in reference sources, its relationship to other existing subject headings, and evidence that the term is both historically accurate and the predominant term currently in use. The proposal is then posted for public comment, usually for about a month. Following the public comment period, Library of Congress staff will either approve, reject, or send the proposal back for revision. Most of the time, proposals are accepted.

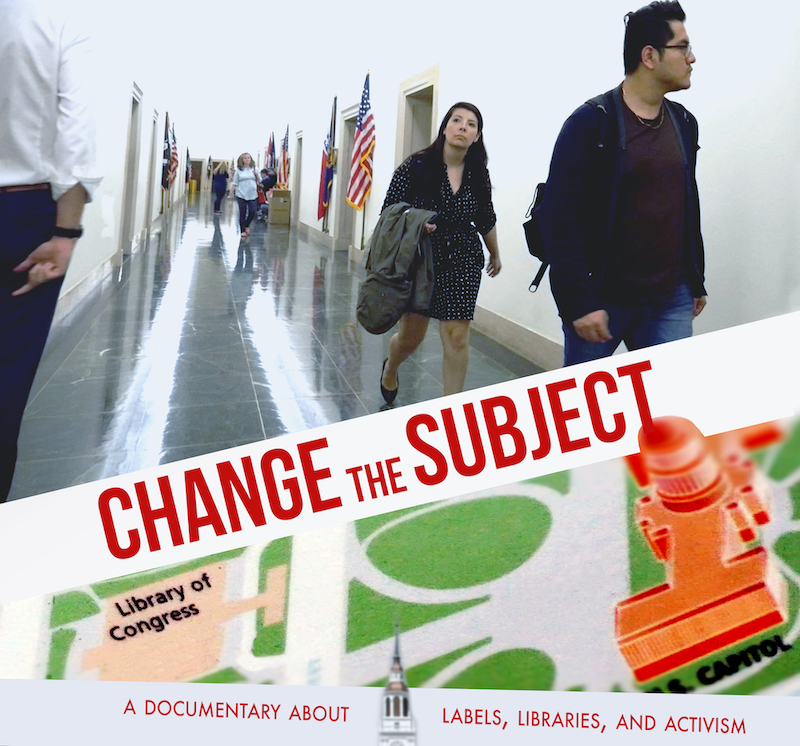

However, language is political, and the Library of Congress is, well, the Library of Congress. Seemingly technical aspects of knowledge organization can become political footballs for government officials looking to score points in the culture wars. This can have serious consequences for the Library of Congress, as Congress controls the Library’s funding and the Librarian of Congress serves at the pleasure of the President of the United States. Library users can be harmed as well. Change the Subject, a 2019 documentary about a group of Dartmouth College students lobbying to change a subject heading that is derogatory to undocumented immigrants, is well worth watching. After a political backlash that included the introduction of the first ever legislation to block the revision of a Library of Congress Subject Heading, the Library of Congress has yet to follow through with the subject heading change it approved five years ago.

Some libraries, including Columbia University Libraries, have instead chosen to make local changes to remove this harmful term from our catalogs. At Columbia, we decided to replace the term and 22 other related terms in the display layer of CLIO with locally preferred alternative terms. This allows us to retain the information retrieval benefits of using the same system of controlled subject headings as thousands of other libraries across the country and around the world. The primary drawbacks are that the harmful term is still displayed in staff-facing systems (librarians are people too!) and in external systems that may be accessed via links in CLIO.

Why use subject headings at all? Controlled vocabularies, of which subject heading systems are one type, are a powerful information retrieval tool. This would be true even in a library where the full text of every resource was searchable. Subject headings improve the accuracy of subject-based searches by creating a one-to-one correlation between a concept and the authorized term used to describe it. This eliminates free-text searching problems such as variant spellings, synonyms, homophones, and homographs (words with the same spelling but different meanings, e.g. “pen,” which can be a writing instrument or a fenced area). It also facilitates searching across multilingual collections of resources, or resources without searchable text, such as musical scores or images. When many libraries use the same system of controlled subject headings, such as LCSH, users who learn the system at one library can use it at others. Users can also search union catalogs such as WorldCat and archival metadata aggregators such as ArchiveGrid or Archives West, and locate relevant material at every library and archives that contributes metadata to the resource.

For me, the operative question is, why use Library of Congress Subject Headings? Following the incident documented in Change the Subject, the Library of Congress has rejected proposals to revise headings such as “Indians of North America” and “Slaves,” and to create new headings for concepts including “Toxic masculinity” and “White fragility.” This spring, it did approve the University of Oklahoma Libraries’ proposal to revise the heading formerly called “Tulsa Race Riot” to the more accurate “Tulsa Race Massacre.” How does this seemingly arbitrary record of decision-making affect library users’ trust in librarians and in the accuracy of the metadata we create? Do LCSH’s virtues truly outweigh its harms, or is the entrenched whiteness of librarianship putting its thumb on the scale yet again?

What are the alternatives? Supplementing our use of LCSH with specialized controlled vocabularies and thesauruses such as Homosaurus and the American Folklore Society Ethnographic Thesaurus is one option. As Karen Smith-Yoshimura notes, though, the hierarchies at issue in ontologies and thesauri prevent this from becoming a universal solution. Linked data can help by using Universal Resource Identifiers (URIs) as proxies for controlled terms in the one-to-one correlation that gives controlled vocabularies their value. For example, as long as every participating library includes http://id.loc.gov/authorities/subjects/sh85123347 in their authority records, searches will locate all materials associated with that subject heading regardless of whether the label associated with the URI is “Slaves” or “Enslaved persons.” (This is essentially a different route to the same result as altering the public display layer of the library catalog.) FAST—a simplified subject heading system linked to LCSH but managed by OCLC, a nonprofit library cooperative which also manages WorldCat and ArchiveGrid—could do exactly this. FAST does not yet provide alternative labels for LCSH terms, however. All of these alternatives require widespread adoption and investment to succeed.

In the meantime, libraries have demonstrated that we are able to implement local changes that create an affirming searching and browsing experience for all of our users. I hope this success encourages us to undertake more ambitious inclusive cataloging and archival description work. We still have a long way to go.

Thanks to my colleagues Michele Wan, Matthew Haugen, and Stuart Marquis for their thoughtful and accessible explanations of the LCSH review process and the CLIO display layer changes.

3 thoughts on “On Outdated and Harmful Language in Library of Congress Subject Headings”

Comments are closed.