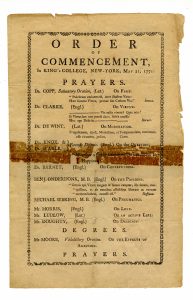

At the RBML, we recently installed a small exhibition on diplomas awarded by King’s College, as Columbia was known from 1754 to 1784. The exhibition in the Chang Octagon features reproductions of diplomas awarded from 1763 to 1773. It also includes related documents: a handwritten draft for an honorary degree, a program from the 1771 Commencement, and even the lists of names sent to the engrosser or copyist to create the year’s diplomas.

Receiving a diploma upon the completion of a degree is nowadays a well-known tradition but that was not necessarily the case back in the eighteenth century. In fact, at Harvard, students were not given diplomas upon graduation until 1813. Before that, students had to purchase their own parchments and pay a professional calligrapher to design and engross their diplomas. At King’s College, the diploma tradition was adopted earlier, with the arrival of President Myles Cooper in 1763. At the University Archives, we have King’s College diplomas from 1763 to 1774, all bearing the signature of Myles Cooper, the second President of King’s College.

The Material

The diplomas are engrossed or written by hand on sheepskins which are about 8 inches long and 13 inches wide. The measurements are approximate since the skins come in irregular sizes and also tend to shrink and buckle over time, especially depending on the environmental conditions. In 1790, the trustees of Columbia College switched the printing of diplomas to parchment, which would be used for the next hundred years.

The Text

The diploma text is in Latin, just as Columbia College diplomas are to this day. The text follows a set formula in which the only terms that change are the recipient’s name, the degree received (AB or AM), and the commencement date. The text can be rendered in a clear cursive script but it is more commonly reproduced in a more elaborately adorned calligraphy.

We have in our collections some of the lists of graduates that were sent to an engrosser or copyist to prepare the diplomas. These lists include the names organized by degree and a quick note at the bottom notes the commencement date. Because the text is in Latin, the first names of the recipients are Latinized so that John Jay becomes “Johannes Jay.” And, for those who took Latin, because the first name is the object of the verb, it appears in the accusative case, “Johannem Jay.”

The Degrees

At the very first public Commencement in 1758, President Samuel Johnson awarded an impressive 21 degrees. Back then, diplomas were awarded not just to students who completed their ABs. In fact, only 5 of the first graduating class had studied at King’s College. In those days, there was the tradition of ad eundem degrees: graduates of other colleges could apply (and for a fee) receive the same degree from another college. In 1758, one AB student had been educated at the College of Philadelphia (now the University of Pennsylvania) and two AB students “in the Jersey College” (now Princeton University). Some of the AM recipients came from Harvard, Yale, Oxford and Cambridge.

In addition to the ad eundems, AMs were awarded as honorary degrees to new faculty members and to prospective or ordained Anglican priests. Once the College was old enough, alumni could apply and receive (for a fee) an AM degree three years after their own graduation. What we now know as a Master’s graduate degree did not exist until the 1860s.

The Seal

Hanging from a ribbon attached at the center of the lower band is a wax impression made from the College seal. The seal was designed by King’s College first president Samuel Johnson. We have in our collections the metal die or the engraving of the seal which was used to create those impressions. The die was a gift to the College by a Mr. George Harison in 1756. (The seal cost Mr. Harison 10 guineas!) The current seal is identical to the King’s College seal in all respects, except for the name: Columbia University.

The Signature

At the bottom of the skin or page, the parchment is folded over. On this thicker or double band, the President of the College adds his signature. The Samuel Verplack KC 1758 diploma is the only known one to have President Samuel Johnson’s signature. (This diploma is held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.) In our surviving examples, the signature belongs to Myles Cooper LLD, President of King’s College in New York.

There was no public Commencement in 1775 “on account of the absence of Dr. Cooper,” a loyal Tory who left New York rather hastily, escaping the City aboard a British warship earlier that year. The following year, in 1776, because of “the turbulence and confusion which prevail in every part of the Country,” there was again no public Commencement ceremony. However, we do have in our collections the list of names sent to the engrosser, so that diplomas could be prepared for these students. A note at the bottom of the Class of 1776 list of names states that the diplomas were sent to Acting President Benjamin Moore. King’s College was closed in 1776 and reopened as Columbia College in 1784.