The Xi’an Incident/西安事變 is also known as one of the most controversial historical events in 20th Century Chinese history. This event led to the united forces between the Chinese Nationalists and the Communists in 1936 December prior to the all war against Japan aggression in China during WWII. In the midst of the incident, William Henry Donald (端納), an Australian journalist who was a close friend of Zhang Xueliang (Peter H. L. Chang/張學良), and the mediator between Zhang Xueliang, Chiang Kai-shek, and Yang Hucheng, as well as many other who were involved.

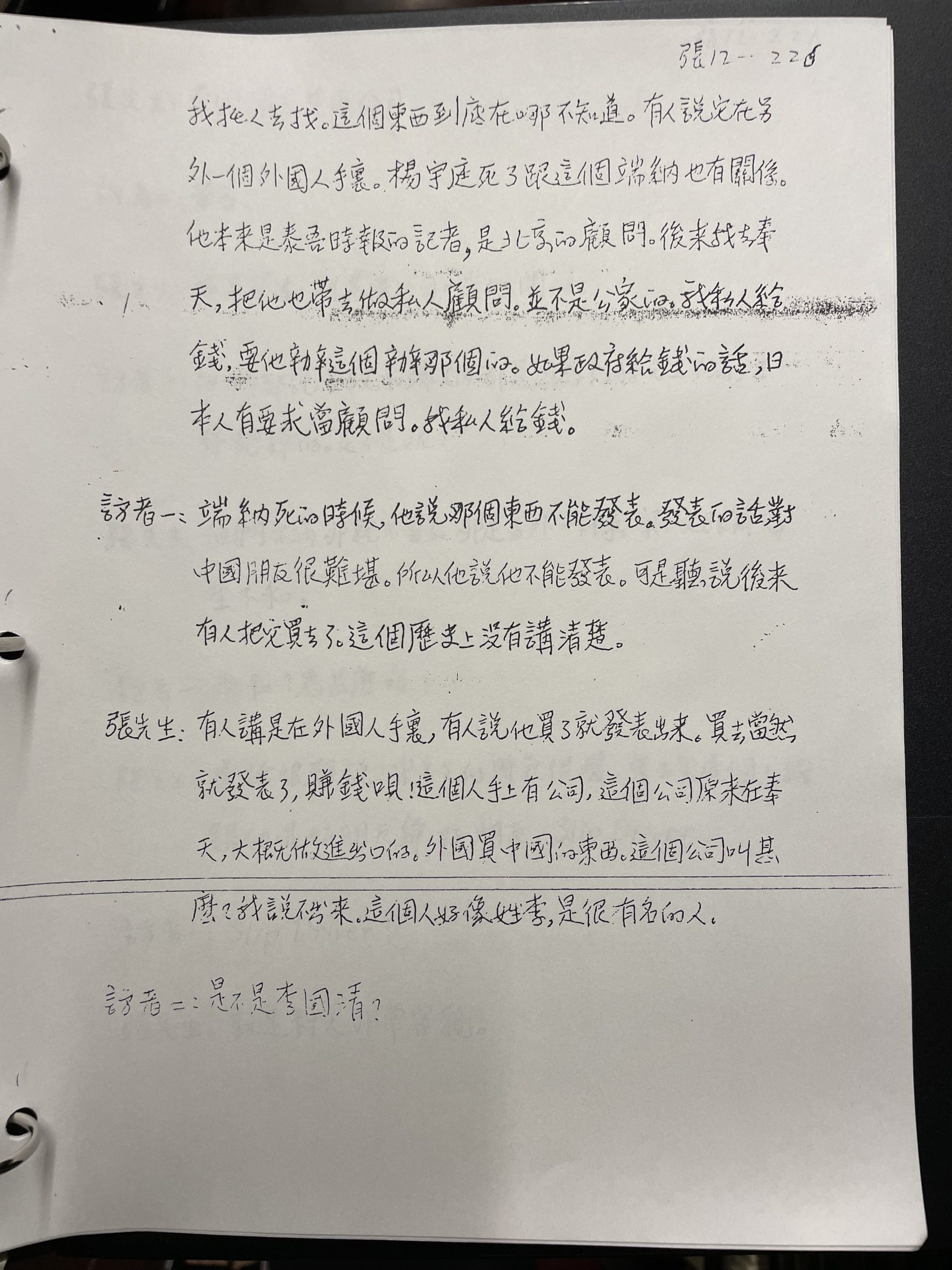

The William Henry Donald letters consist of letters dating from 1924 to 1946. Most of the letters were sent by Donald to his friend Harold K. Hochschild (1892-1981), a long-time friend of Donald with personal and business interest in China, he was also the Executive of the American Metal Company in New York. The letters were later donated to Columbia through the Estate of Harold K. Hochschild via the East Asian Institute in 1982. Included in the collection are letters, biographical information, a sketch of Donald and a photograph of his grave in China, as well as news clippings about Donald’s death and his involvement in Chinese politics.

Left: Sketch of Donald, Inscribed to Harold K. Hochschild, from Shanghai, May 24, 1946. William Henry Donald papers. Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University Library. Right: Photograph of Chinese delegates of the Lytton Commission in Northeastern China, 1932-1933. Front row (R-L): V. K. Wellington Koo/顧維鈞, Liu Chongjie/劉崇傑, Harry Hussey; back row (R-L): Wu Xiufeng/吳秀峯, Xiao Lianggong/蕭亮功, Shi Zhaokui/施肇夔, W. H. Donald/端納. V. K. Wellington Koo papers; Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University Library.

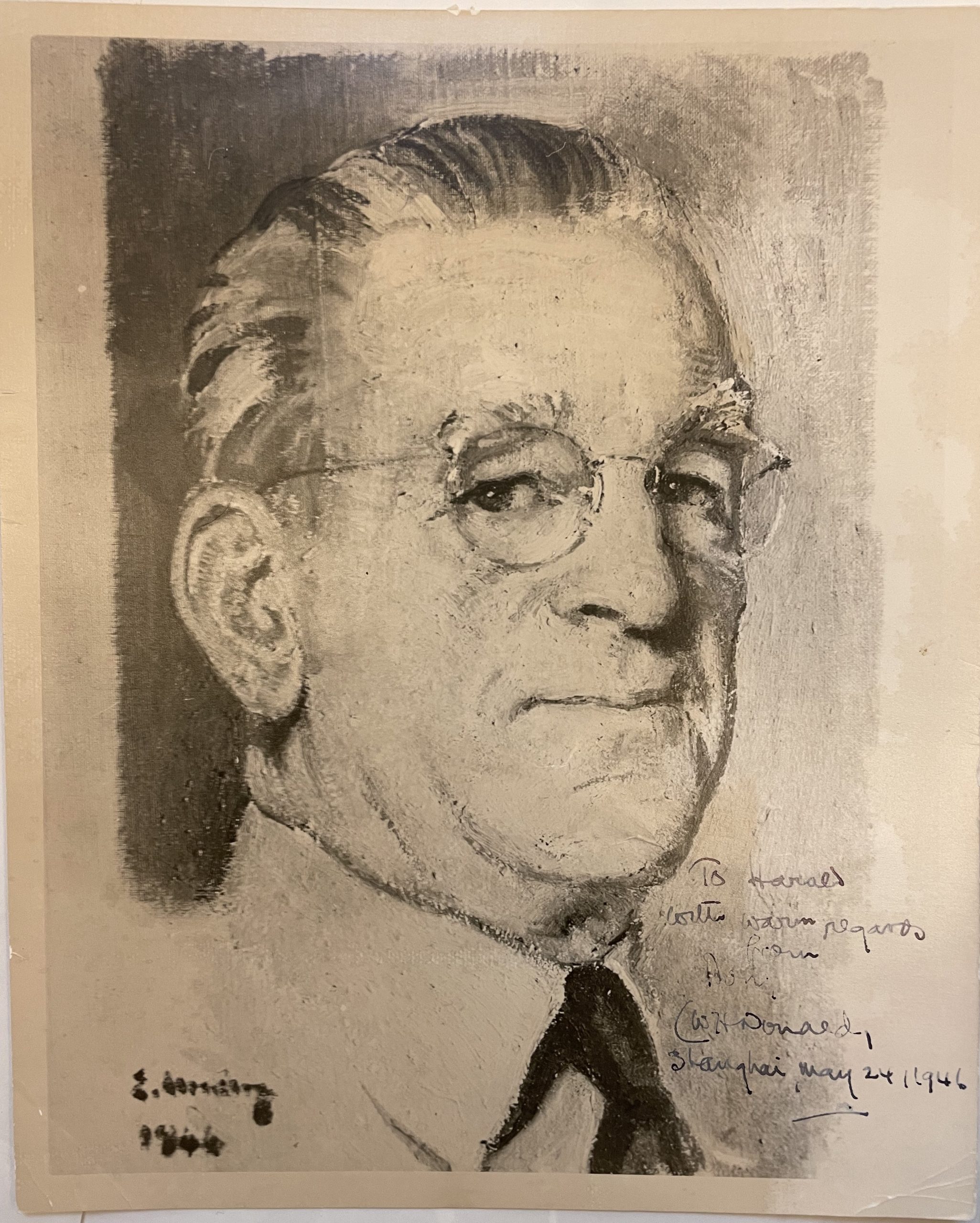

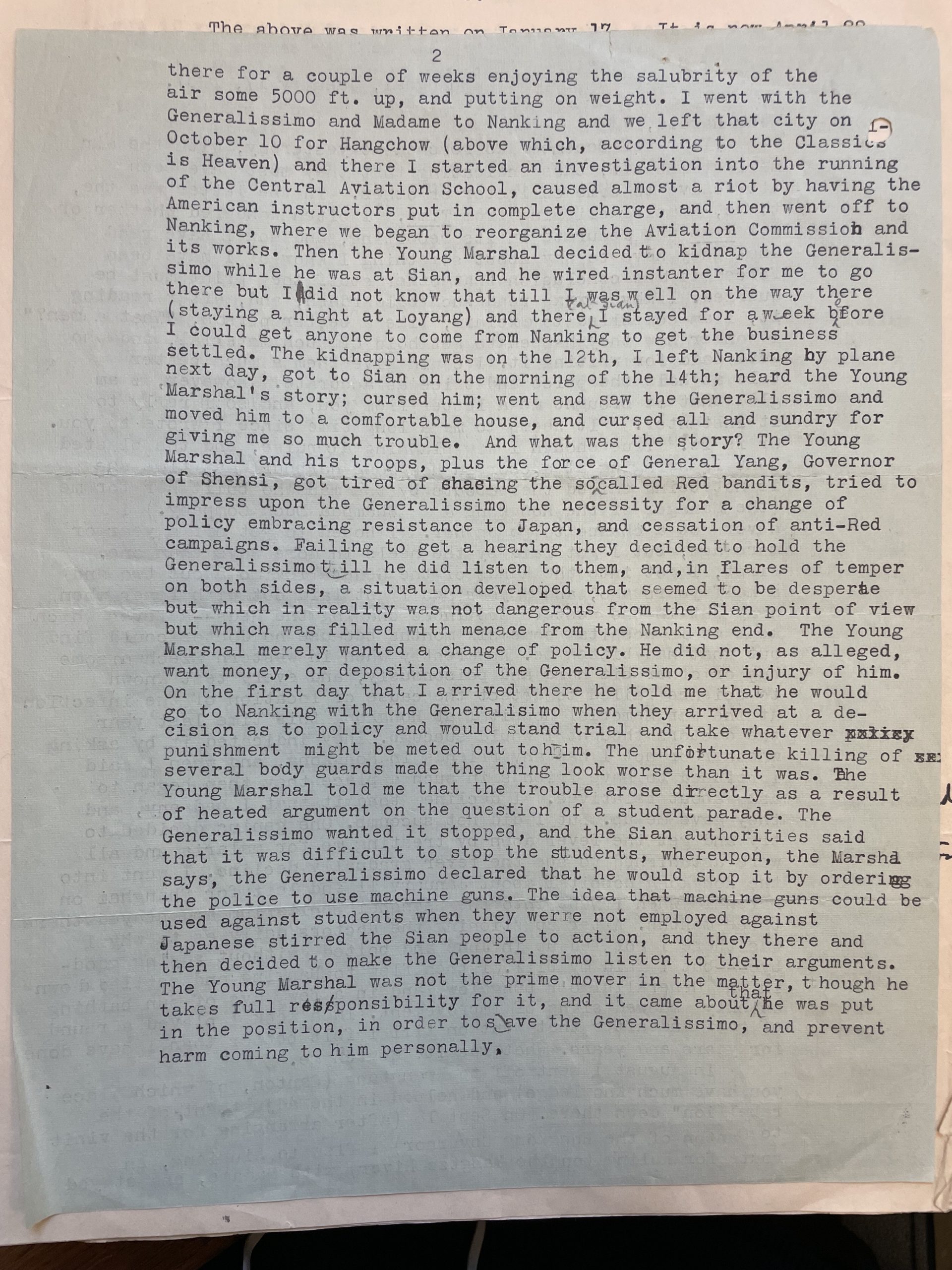

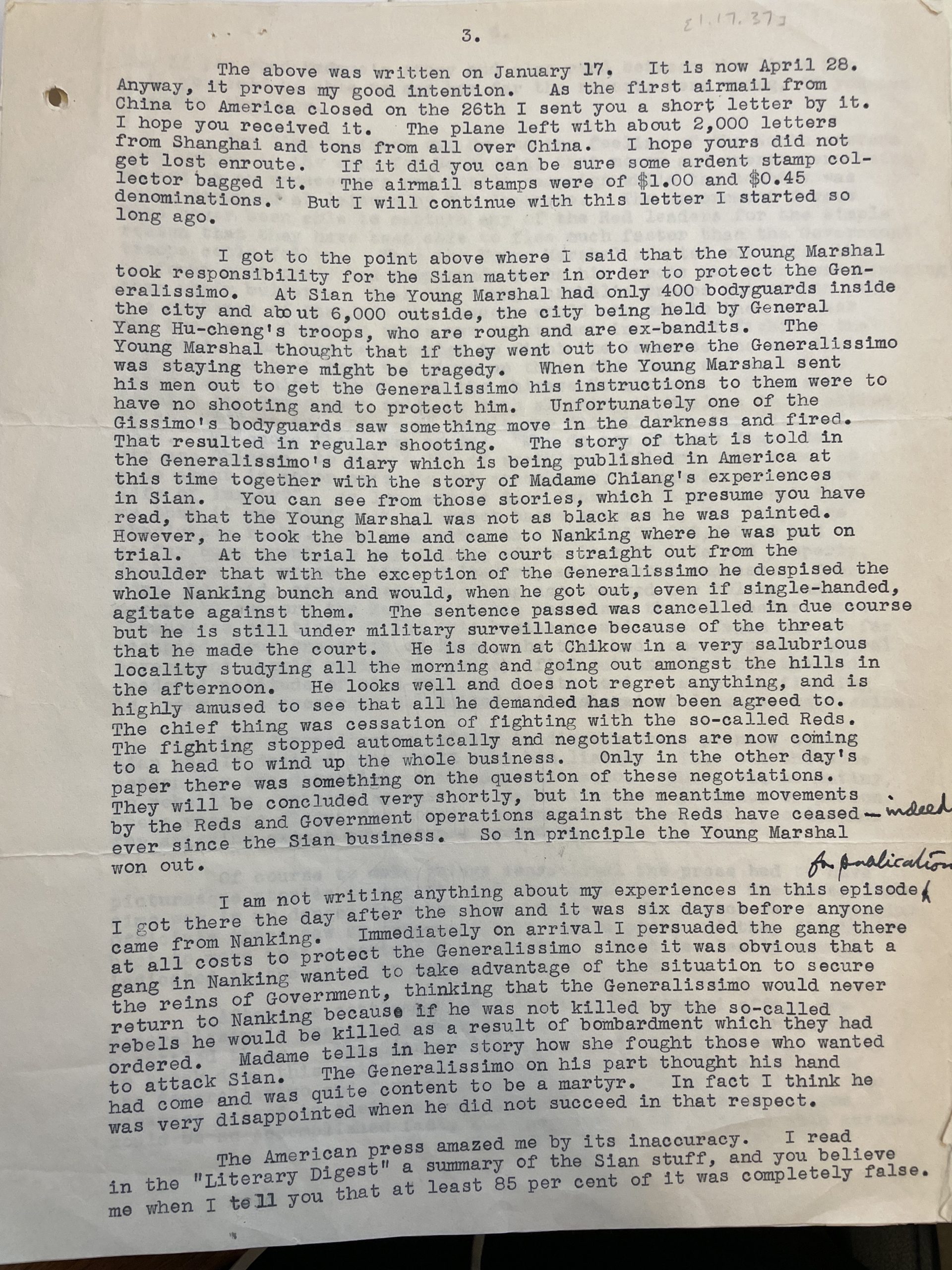

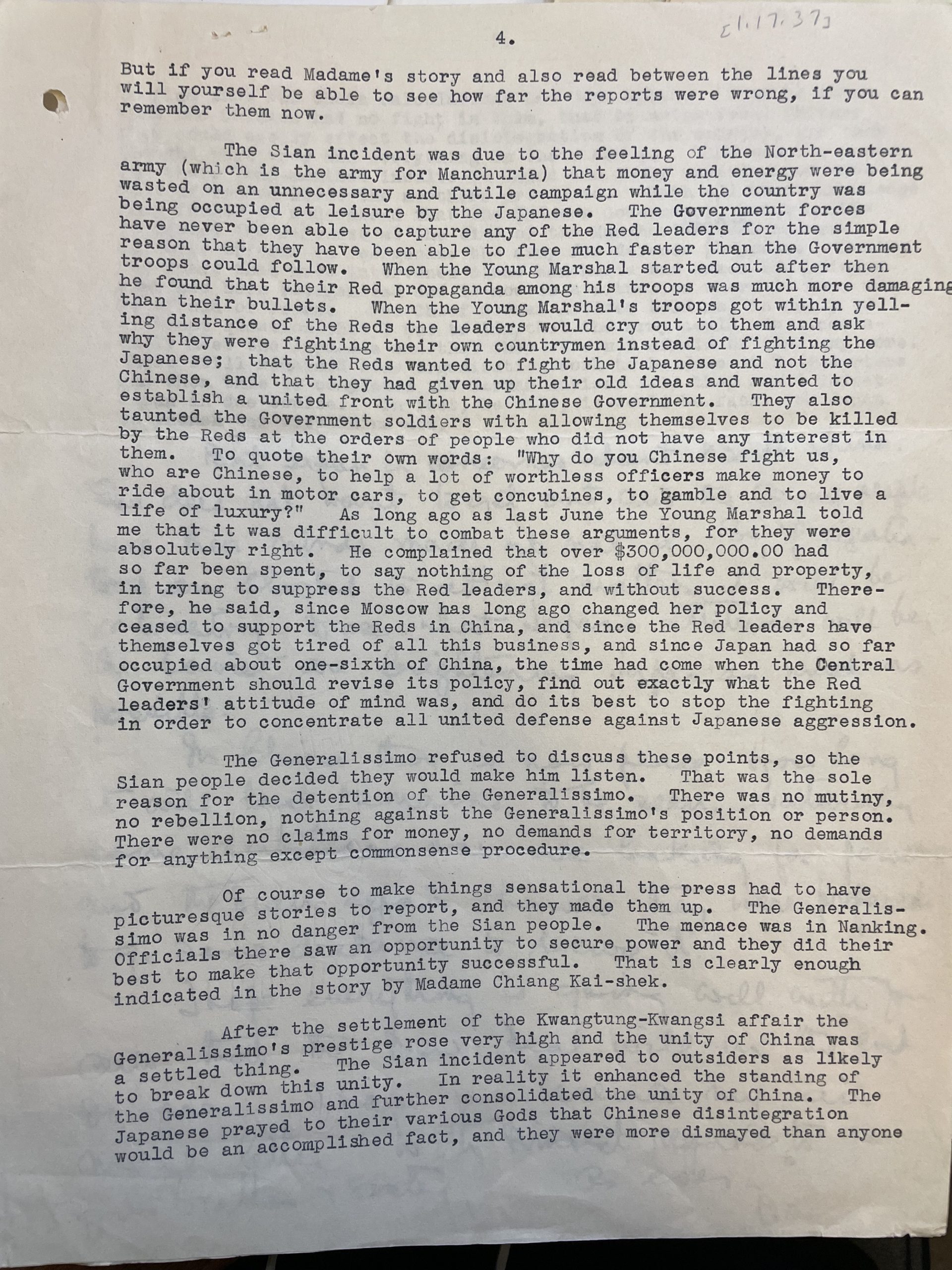

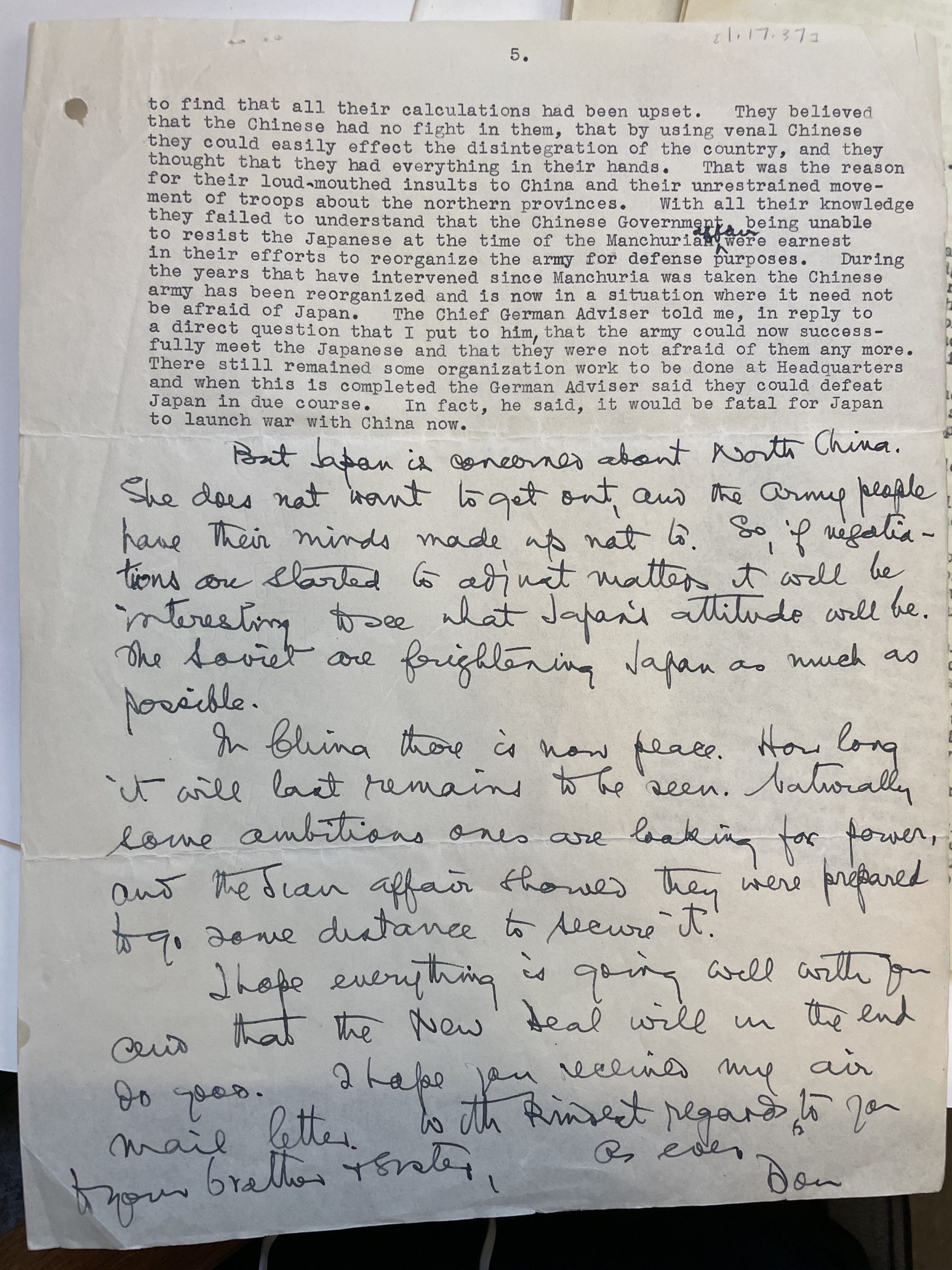

Donald’s letters are informative about his life and his views on Chinese politics at the time. The most interesting set of letter is the five-page letter he wrote to Harold on January 17 and April 28, 1937 describing the Xi’an Incident as he witnessed and experienced it. The following are some excerpts of his account about the incident from the letter.

“Then the Young Marshall decided to kidnap the Generalissimo while he was at Sian, and he wired instanter for me to go there but I did not know that till I was well on the way there (staying a night at Loyang) and there at Sian, I stayed for a week before I could get anyone to come from Nanking to get the business settled. The kidnapping was on the 12th, I left Nanking by plane next day, got to Sian on the morning of the 14th; heard the Young Marshal’s story; cursed him; went and saw the Generalissimo and moved him to a comfortable house, and cursed all and sundry for giving me so much trouble.”

“And what was the story? The Young Marshall and his troops, plus the force of General Yang [Hucheng], Governor of Shensi [Shaanxi], got tired of chasing the [so-called] Red bandits, tried to impress upon the Generalissimo the necessity for a change of policy embracing resistance to Japan, and cessation of anti-red campaigns. Failing to get a hearing they decided to hold the Generalissimo till he did listen to them, and in flares of temper on both sides, a situation developed that seemed to be desperate but which in reality was not dangerous from the Sian point of view but which was filled with menace from the Nanking end. The Young Marshall merely wanted a change of policy. He did not, as alleged, want money, or deposition of the Generalissimo, or injury of him.”

“On the first day that I arrived there he told me that he would go to Nanking with the [Generalissimo] when they arrived at a decision as to policy and would stand trial and take whatever punishment might be meted out to him. The unfortunate killing of several body guards made the thing look worse than it was. The Young Marshall told me that the trouble arose directly as a result of [a] heated argument on the question of a student parade. The Generalissimo wanted it stopped, and the Sian authorities said that it was difficult to stop the students, whereupon, the Marshall says, the Generalissimo declared that he would stop it by ordering the police to use machine guns.”

Below are the full 5-page letter of Donald’s account:

William H. Donald to Harold K. Hochschild, Shanghai, January 17, 1937, April 28, 1937; William Henry Donald letters.

In addition, the Peter H. L. and Edith Chang papers contain an album of collected news clippings dated 1946 dedicated to Donald (Box 31 Folder 05.01). The RBML also holds the Zhang Xueliang oral history interviews. In his oral history interview with Tang Degang (T. K. Tong) in 1991, the transcript mentions that he knew about the letters and writing that Donald wrote about the Xi’an incident. They were “rumored” to have been purchased by an American businessman with business ties in China at the time, and promised not to disclose the writings 50 years after his death. Harold K. Hochschild, who was Donald’s close friend, was most likely the businessman that Zhang mentioned in the oral history interview. Harold passed away in 1981 and the letters were donated to the East Asian Institute in 1982, and then transferred to the RBML after.

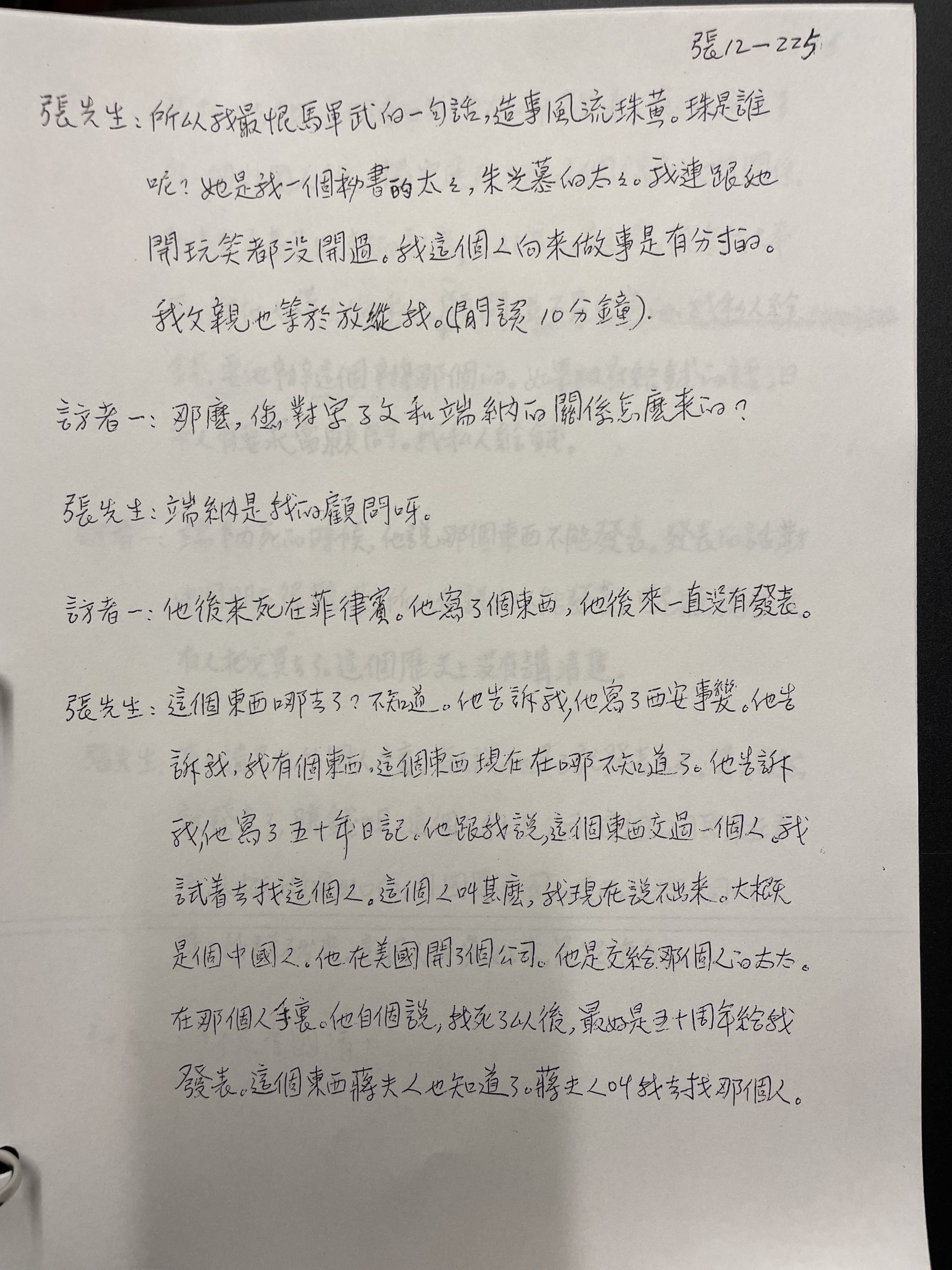

From Zhang Xueliang oral history transcript with Tang Degang (T. K. Tong), 1991, Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University Library.

This controversial incident led to the unification of the Chinese Nationalist and the Communist forces prior to the all out War against Japanese Aggression in China. After the Xi’an Incident, Yang Hucheng 楊虎城 was imprisoned for 13 years until Chiang Kai-shek ordered him and his family executed before retreating to Taiwan in 1949. Zhang Xueliang was under house arrest for over 50 years in mainland China and Taiwan before emigrating to Hawaii to be with his family in 1993. As for Donald, he was later held captive in the Japanese prison camp in Manila, Philippines, around the same time of the death of a Chinese diplomat, Clarence Kuangson Young (Yang, Guangsheng 楊光泩) in 1942. Donald was released from the camp in 1945. He died in 1946 and was buried in the Song Qingling Cemetery in Shanghai. As a mediator in the midst of a historical turning point in China, Donald’s letters to his friend Harold offer a close look at his life, his personal experiences, as well as his interpretations of historical events, including his close association with some of the major political figures in modern Chinese history.

For more information about the William Henry Donald letters, the finding aid is available here.

Additional reading: Selle Earl Albert. Donald of China. 1st ed. Harper 1948.