Laura Fisher Kaiser, author and independent researcher, recently visited the RBML as part of her work on a new biography of novelist Frances Elizabeth Budgett, pen name Elizabeth Dejeans. Kaiser discusses some of her finds for The Fabulous Invention of Jazz-Age Novelist Elizabeth Dejeans in the Paul Reynolds literary agency collection below:

What  brings you to Columbia’s Rare Book & Manuscript Library?

brings you to Columbia’s Rare Book & Manuscript Library?

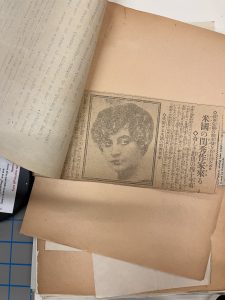

The Paul R. Reynolds literary agency records, 1899-1980. I am working on the first biography of novelist Frances Elizabeth (Janes) Budgett (1868-1928), whose pen name was Elizabeth Dejeans. Of her twelve novels and numerous short stories, three were adapted to the silent screen in Pre-Code Hollywood, and her grande dame persona was a fixture on the California “society” circuit. However, when she died, she left no descendants or papers and has been all but forgotten. I have been piecing together her life mainly through hundreds of newspaper articles by and about her in online databases, as well as from papers in various archives. In one of the latter (Bobbs-Merrill mss., Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana), I found a couple of letters from her agent, Paul Revere Reynolds. I thought, “Who is this dude?” A big deal, it turns out! He practically invented the literary-agent industry in America and played a major role in the careers of many famous writers including Willa Cather, Stephen Crane, George Bernard Shaw, H. G. Wells, Joseph Conrad, Leo Tolstoy, P. G. Wodehouse, Dorothy Canfield, Richard Wright, Ellen Glasgow – the list goes on. This led me to his papers at Columbia’s RBML. The RBML finding aid indicated an “Elizabeth Dejeans” folder, so I knew I had to check it out.

How long have you been using RBML materials (for this and/or previous research)?

This was my first time at RBML. Since Dejeans published one book with Harpers (The Life-Builders, 1915), I also looked at RBML’s Harper & Brothers Records, 1817-1929, but there was nothing on her. The Reynolds papers, however, were a goldmine. I was overwhelmed with gratitude that Paul Reynolds kept such meticulous files (down to the cost of stamps), and that the RBML has archived these papers so carefully and makes them available to independent researchers like me.

What have you found? Did you come here knowing this material was here?

When you go into an archive you often don’t know whether you’re going to find a treasure trove or a sad thin folder with little more than a blurb, so I was thrilled to be handed four oversized folders stuffed with correspondence between Dejeans and Reynolds. More than 800 letters, as well as ledger accounts and a few random manuscript bits, that spanned her entire career from 1908 to 1928. He always comes off as the unflappable voice of reason, even when she is going off about some perceived outrage.

What have you found that’s surprised or perplexed you?

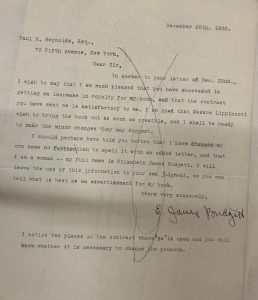

When she first queried Reynolds in 1908, she signed her letters “E. Janes Budgette,” which made him assume that she was a man. It wasn’t until he sold her first novel (The Winning Chance, to J. B. Lippincott Company) that “E.” revealed that she was a woman. In the course of the next few letters, we can see how she came up with the nom de plume of “Elizabeth Dejeans,” which in time became her fabulous alter ego. Literary agents were a new concept in early 20th-century America, so it’s amazing that she had the perspicacity and audacity to approach Reynolds before she had published a single thing. But Reynolds saw something in her and supported her as a friend and colleague to the end.

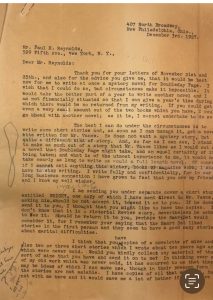

However, her last few letters to Reynolds in 1927 make for painful reading. After failing to find a buyer for her latest manuscript, he explains, “One criticism was that there were too many ‘dubious’ ladies in it.” This, after she’d built a career writing about such risqué subjects as adultery, divorce, unwed mothers, and dope rings! Here she is, 60 years old, broke, without any family or means of support, sinking into one of her debilitating depressions. She tells Reynolds that if he can’t sell something soon, “I shall have to stop writing.” He tells her to buck up, not realizing, I think, how desperate she is – or that suicide runs in her family. He has no way of knowing that two months later she will take her own life. That last letter to him is the closest thing I’ve found to a suicide note and it gives me chills.

What advice do you have for other researchers or students interested in using RBML’s special collections?

What advice do you have for other researchers or students interested in using RBML’s special collections?

Archives in general can be a tough nut to crack because many materials are by definition idiosyncratic and only take on significance when placed within the context of other research. I’m always amazed by what librarians know, or don’t know but are excited to discover, because all research is an ongoing conversation. It helps to have done some homework so you know the right questions to ask. As an independent researcher working on a book about a figure few people have heard of, I’m probably guilty of not relying on the expertise of librarians enough. When I requested the Reynolds files, it was a shot in the dark, to be honest, because Elizabeth Dejeans is so obscure and, aside from the RBML archivists, I might well be the first person to have ever delved into her correspondence. Perhaps there is even more at RBML to be found? I hope so – I would love to come back. My one other tip: bring a phone charger.