The Watts Towers exemplify how the vision of an artist can transform the built environment while creating a world of its own. The art environment was created by the Italian Sabato (Simon / “Sam”) Rodia at his home in the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles and includes the iconic two towers, a gazebo, walkways, and fountains. The structures were built using steel and mortar and decorated with discarded glass bottles, pottery shards, and other found material Rodia collected.

The Watts Towers exemplify how the vision of an artist can transform the built environment while creating a world of its own. The art environment was created by the Italian Sabato (Simon / “Sam”) Rodia at his home in the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles and includes the iconic two towers, a gazebo, walkways, and fountains. The structures were built using steel and mortar and decorated with discarded glass bottles, pottery shards, and other found material Rodia collected.

Because of his endeavors and the environment’s grandeur, Rodia became a well known figure but would abandon his creation in 1954 to live the rest of his life in Martinez, California. The environment was nonetheless loved by many and through the perseverance of admirers, the entire site is still preserved in its original location.

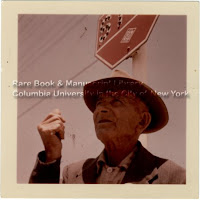

One such admirer was Kate Steinitz who took a photograph of Rodia and sent it to Meyer Schapiro. Steinitz was also an artist in her own right, she began her artistic endeavors in Hanover, Germany working with the likes of Dadaist Kurt Schwitters. Steinitz is more famously known as the world renowned Leonardo Da Vinci scholar who worked at the Elmer Belt Library of Vinciana located at UCLA.

One such admirer was Kate Steinitz who took a photograph of Rodia and sent it to Meyer Schapiro. Steinitz was also an artist in her own right, she began her artistic endeavors in Hanover, Germany working with the likes of Dadaist Kurt Schwitters. Steinitz is more famously known as the world renowned Leonardo Da Vinci scholar who worked at the Elmer Belt Library of Vinciana located at UCLA.

Given her background in the Dada and Surrealist art movements, Steinitz may have felt an affinity with Rodia’s art environment. She was, in fact, the archivist of the Watts Towers Committee.

Steinitz wrote, “Sam, though opposed to machines, tolerates the camera, but he does not pay much attention to it. Anytime I step back to get at least a distance of 3 feet, Sam follows me, apparently concerned to not lose a listener.”

Steinitz was also friends with another Rodia admirer and photographer, Seymour Rosen, who actively documented the environment and championed for its preservation.

On the verso of this photograph, Steinitz would write to Schapiro:

On the verso of this photograph, Steinitz would write to Schapiro:

“Sam Rodia says: Why did Meyer Schapiro avoid Los Angeles? The towers are waiting.”

It remains to be seen if Schapiro did visit the Towers, although, as of yet, I can’t find evidence of that.

In the meantime, the Watts towers are still waiting and can be viewed in person.

For those of you who can’t make it, this documentary created in the 1950s shows the neighborhood as it was back then and includes Rodia working on his creation.

Update:

The Los Angeles Times reported that a two hour town hall meeting took place on July 16, 2009 and included spokespersons from the Los Angeles Cultural Affairs Commission and the Cultural Heritage Commission addressing the conservation and preservation needs of the Watts Towers. According to the Times, both entities “voted unanimously to send a letter to Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa, asking him to help recruit donors and activists for a private, nonprofit support group akin to ones that help fund the Los Angeles Zoo and Griffith Park Observatory.”

Conservation advocates have been at odds with the financial and conservation support the the City of Los Angeles is giving to the site. This came to a head in April 2009, at a conference in Genoa, Italy titled “Art and Immigration: Sabato (Simon) Rodia and the Watts Towers of Los Angeles.” Reports from Virginia Kazor, historic site curator for L.A.’s Department of Cultural Affairs and the Committee for Simon Rodia’s Towers in Watts represented conflicting reports. Kazor’s report “Triage: the Challenge of Conserving the Watts Towers” underlined the financial shortage while the Committee’s report “Damage in Process” highlighted the lack of ethical conservation methods employed in the environment’s upkeep.