We see them every day, handing them a key as they walk in each morning, and receiving it back toward the end of the day. Most often they are hunkered down over a particular archive, getting to understand a portion of one of our archives better than anybody here. We await the longer scholarly projects that they are developing from this research but in the nearer term thought it would be interesting to give a preview of their work.

In this brief interview, Curator for Literature Karla Nielsen, asked Wouter Capitain about his research in the Edward Said Papers. He’s visiting Columbia’s Music Department as a Fulbright Scholar from the University of Amsterdam.

Wouter Capitain first showed up in the Columbia RBML this past January. He is here for three months as a Fulbright scholar to do research on the Edward Said Papers. He is working on his doctoral dissertation at the Amsterdam School for Cultural Analysis (University of Amsterdam). Edward Said was internationally recognized as a literary critic and postcolonial theorist but less well known is his work related to music. Wouter Capitain’s research foregrounds Said’s interest in music, both as a performer and critic, and offers a re-reading of Said’s significance from that perspective. He proposes a contrapuntal theory of reading an archive that should have resonance beyond this particular project.

What is your research project?

I am writing my PhD dissertation about Edward Said’s work on music and its interactions with his theoretical and political engagements. I try to understand Said’s “work” or oeuvre as broadly as possible, not restricting it to his published output. The Edward Said Papers offer me the opportunity to study his unpublished work, such as teaching materials and personal correspondence. In this study I am influenced by Said’s “contrapuntal” perspective by paying attention to how different voices interact and overlap. Within the archive, I study the interactions between his various musical, theoretical, and political engagements, and his different professional activities as an author, teacher, and public intellectual.

How did you become interested in Edward Said?

I have a background in musicology, yet I am not necessarily interested in music as such but rather in how music interacts with other domains, and specifically with social and political issues. Many scholars have studied the ways in which society has an impact on music, but Said was also interested in how music has the potential to influence society. Through my former professor Rokus de Groot I became acquainted with Said’s writings about music and I wrote my master’s thesis about Said’s essay on Verdi’s Aida. I continued this research for my PhD dissertation on his work on music in general. Although many scholars have already written about Said, my dissertation will become the first book-length study of his work on music.

With a “contrapuntal” perspective on his work I try to demonstrate that Said had multiple voices which interact and overlap with each other, sometimes sounding harmonious but at other times dissonant. The archive enables me to study the interactions and tensions between his different professional activities.

What are you finding in the archive that is relevant to your project?

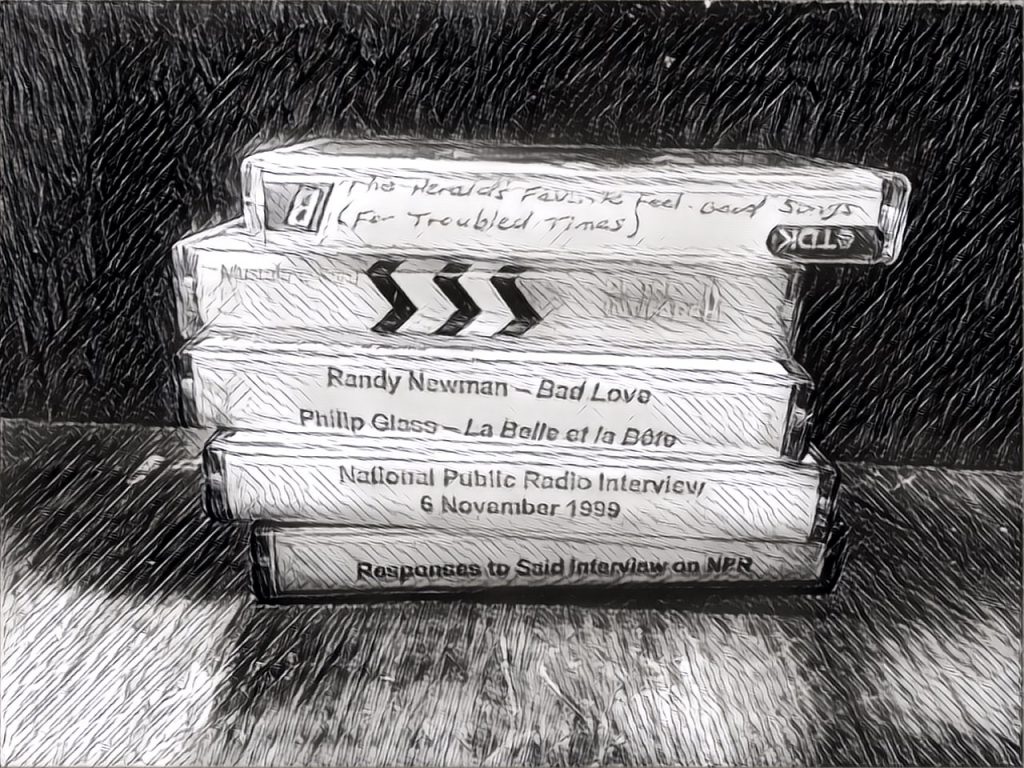

Much more than I can deal with in only three months. I am interested in the development of Said’s ideas about music and society, and the archive includes many documents that help me to trace these developments. These documents relate to his activities as a teacher, such as course descriptions and teaching notes, but also to his published writings themselves. For example, I have found many different drafts of his essays and books, as well as outlines and book proposals, which demonstrate the genesis and development of his ideas before they were published. In these three months I do not have the time to study all of these documents in detail, but I have already taken over fifty thousand words of notes and have photographed hundreds of documents which I will study more closely back home.

What is the most interesting thing that you have found in the archive? The most surprising?

I find Said’s handwritten drafts most interesting. Said always wrote with a pen; he didn’t use a typewriter or a computer. Obviously his published writings are typed out, but that was done by his assistant, who was Zaineb Istrabadi for most of Said’s later career. She would type out his handwritten draft, hand it back to him in print, and he would make handwritten corrections and additions, which she would incorporate in the typed version. This process would be repeated for perhaps three or four drafts before the text was finished, and most of these drafts are in the archive. It is thus relatively easy to trace how Said’s texts developed, although his handwriting is sometimes difficult to read. Interestingly, Said’s first handwritten drafts are often fairly close to the final published version of the text. (By the way, Said’s typed letters, faxes, and emails were also written by his assistant, based on his handwritten notes.)

These materials illustrate that exclusive attention to Said’s published output can be quite misleading.

What I find most surprising is that Said was in frequent contact with musicologists. In his published writings it seems as if he was criticizing musicology from a distance, because he was of the opinion that the discipline was not paying sufficient attention to the social and political aspects of music, but from his personal correspondence it becomes clear that he was actively intervening within musicology. These materials illustrate that exclusive attention to Said’s published output can be quite misleading. He supported young and progressive musicologists in early stages of their career, for example by helping them to get their research published and by writing letters of recommendation. Besides, he evaluated the Music Department of Columbia in the late-1980’s and was on a number of tenure committees related to musicology, although the access to some of these documents is restricted. Even though I have studied Said’s writings for several years, I was not aware of the extent to which he directly interacted and intervened in musicology.

How do you think your project will change the way that we think about Edward Said?

Said’s work is often read rather monophonically, where the wide scope of his professional activities is reduced to just one publication, Orientalism (1978), and where his complex identity is similarly reduced to a singularity, Palestinian. With a “contrapuntal” perspective on his work I try to demonstrate that Said had multiple voices which interact and overlap with each other, sometimes sounding harmonious but at other times dissonant. The archive enables me to study the interactions and tensions between his different professional activities. Although I focus specifically on his work on music, I believe that this contrapuntal approach is also relevant to his legacy in other domains.

Anything else that you want to say?

This archive is enormous, with over a hundred and eighty large boxes full of paperwork. For my research it is extremely helpful that the documents are organized and indexed in a very accessible and systematic way. Without this organization it would cost me much more time to find and research the relevant materials, and I very much appreciate the effort that is spent on the structuring and indexing of the documents.