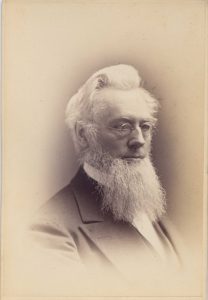

Columbia College’s tenth president, Frederick A.P. Barnard, is best known for paving the way for the College to become a University and for his unsuccessful campaign in support of coeducation. But he has another legacy which is not as well remembered: Barnard made significant contributions in the education of deaf students and he was a progressive deaf educator, textbook author, and an invaluable supporter of deaf students at Columbia.

At the age of twenty, as a recent Yale College graduate, Barnard became a teacher at the Hartford Grammar School. This position served as a 2-year apprenticeship which would allow him to become a Tutor at Yale. It was during this term that Barnard started to experience more significant hearing loss, an affliction he was familiar with from his own mother, a brother and a sister. A young man, Barnard abandoned his plans to go to Law School and started to look for a new profession. After his year as a Yale Tutor, he became a teacher at the American Asylum of Deaf and Dumb in Hartford, CT, which was the first such institution in the US and had been established by Thomas Hopkins Gaulladet. A year later, in 1832, Barnard moved to New York City to teach at the recently opened New York Institution for the Deaf and Dumb (now known as the New York School for the Deaf or “Fanwood”). Here, Barnard taught sign language, arithmetic and geography. In 1834, at the age of 26, he wrote “Education of the deaf and dumb” in the North American Review. With an article in a wide-reaching publication, Barnard aimed to address the existing prejudice and ignorance about deaf people and to promote the establishment of new deaf schools. The following year Barnard reviewed the latest educational trends, including those in France and Germany, in “Existing State of the Art of Instructing the Deaf and Dumb” (1835), an article that was years ahead of its time. He also wrote a textbook, Analytic Grammar, with Symbolic Illustrations (1836), which seems to have been in use in the deaf community through the 1860s.

It is interesting to note that the New York Institution at the time was described as being “out in the country” and “near New York City.” In the 1830s, the City only extended to 10th Street and the Institution was located much further uptown on what would become 50th Street. In 1856, the school moved north to Washington Heights on 162nd Street and 10th Avenue. If the name and, maybe more so, the address of the old Institution sound familiar, it is because in 1857, Columbia College moved from its original campus on Park Place to the New York Institution’s old buildings. This became Columbia’s second campus, on Madison Avenue between 49th and 50th Streets. In the very same buildings, Barnard was first a teacher of deaf students from 1832 to 1837 and then college president from 1864 to 1888.

After his time at the New York Institution, but before he arrived at Columbia in 1864, Barnard served as a professor of mathematics, natural philosophy, chemistry, physics and astronomy at the University of Alabama and later at the University of Mississippi (where he also served as Chancellor or President). Barnard’s scientific contributions cover a wide range of fields. He wrote on the aurora borealis, eclipses, daguerreotypes and stereoscopic photography, pendulum motion, optics, hydraulics, and the metric system. He conclusively defined the state line between Alabama and Florida, set up astronomical observatories at both universities, and was instrumental in the US campaign to adopt standard time or time zones. And he also received orders in the Episcopal Church.

As college president, Barnard helped deaf students enroll at Columbia. One such student was Rowland B. Lloyd, a graduate and then teacher at the New York Institution. Lloyd was admitted to Columbia College as a freshman in 1872. He was excused from attendance on the daily exercises of the class but needed to satisfactorily pass all examinations. Barnard made the arrangements so that Lloyd was “allowed to make all his recitations in writing.” Lloyd completed his first two years but was forced to withdraw during his junior year, when additional work at the Institution made it impossible to be both a full time teacher and college student at the same time. However, Lloyd continued to pursue his studies and Trustees awarded him a BA speciali gratia in 1892.

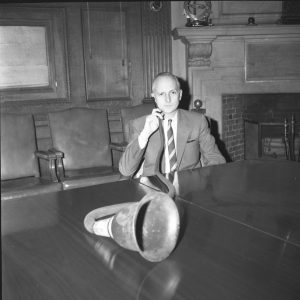

The research shared above was inspired by one item in our collections. At the University Archives we have an ear trumpet or a “Charles C. Currier’s Conico-Cylindrical Conversation Coil” which belonged to President Barnard. This early hearing aid features a six-foot long coil with an earpiece on one end and a large wooden funnel on the other. The ear trumpet did not necessarily amplify sound. Those meeting with Barnard would talk into the cone and it would collect the speaker’s sound waves which would travel through the coil to the earpiece. This device was kept on President Barnard’s desk during his time at Columbia. James C. Egbert, Columbia College Class of 1881, Ph.D. 1884, recalled that using the trumpet was “very awkward when one was particularly anxious to make an impression on [President Barnard]”* but it was available so that students could speak directly to the President. In 1950, Barnard’s ear trumpet returned to Columbia thanks to Mrs. Agnes O’Connor Rossell of Sheffield, Massachusetts, a Barnard descendant.

* Davenport, Charles. “Biographical memoir of Frederick Augustus Porter Barnard, 1809-1889.” National Academy of Sciences Biographical Memoirs, Volume XX, 1938, 265.