This essay was initially printed in the Institute for Israel and Jewish Studies’ 2022 Magazine. The full magazine is available here.

The Sephardic Jews and their descendants were very proud of their cultural heritage. Wherever they traveled, they brought their culture – and languages – with them to their new homelands. Spanish and Portuguese persisted for centuries in Sephardic communities around the world, and these communities built synagogues based on (and often named for) their old communities in Spain. One of the most famous post-1492 Sephardic communities is that of Amsterdam.

Columbia’s Judaica collection includes a very strong collection of materials relating to the Jews of the Netherlands. The backbone of the Judaica collection, donated to Columbia in 1892, originated in Amsterdam, and contains important documents relating to that community.

Sephardic Jews had arrived in the Netherlands as early as the 15th century. There were close connections between Spain and the Netherlands, and King Philip II of Spain controlled the Netherlands from the mid-16th century. However, by time of the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648 of the 17th century, most of the northern Netherlands had achieved independence as the United Provinces. The United Provinces’ joint history with Spain, combined with its break from Catholicism, meant that these lands were familiar to Iberian Jews while also being much more tolerant of non-Catholics. Different cities had different policies regarding Jewish practices, and Amsterdam was well known for its relatively tolerant policies (note that it was not all rosy, though – while Jews were allowed to settle there, they were excluded from many trades). Another critical aspect of Dutch policy by the mid-17th century was that its Jews be recognized as citizens even while abroad, and thus restrictions on Dutch Jews in other lands (including Spain, from which many had fled to revert from Christianity to Judaism!) were necessarily limited.

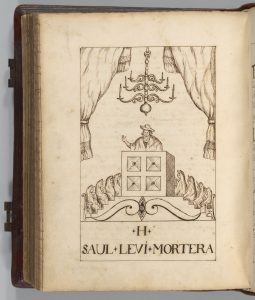

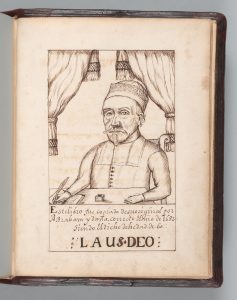

Crypto-Jewish migration to Amsterdam from the Iberian peninsula would continue over the next two centuries. Those Jews who had converted publicly to Christianity to survive in Spain realized that travel to Amsterdam meant that they could return to their Jewish practices and communities. This caused some confusion, however, as these Jews often mixed up Christian and Jewish practices and beliefs. Saul Levi Morteira was an important rabbi and teacher of Judaism, and his book Tratado de la verdad de la ley de Moseh y providencia de Dios con su pueblo was a critical text in teaching the distinct differences between Judaism and Christianity, as well as correct Jewish practice. The image of him teaching in the still-extant Ets Haim yeshiva, from one of our four manuscript copies of the work, is the only known contemporary drawing of the rabbi in existence today. The same volume includes a self-portrait of this book’s scribe: another Amsterdam rabbi, Abraham Idana (Idana and his neighborhood were featured in the 2021 Norman E. Alexander Library Celebration of Collections).

The arrival of many conversos to Amsterdam led to the creation of a number of polemical works (often in manuscript, because Jews printing anti-Christian texts – even in tolerant Amsterdam – would have been a bit too much for their hosts). These “Burlesque Dialogues” between a Reformado (a Protestant), a Catholico, a Turco (that is, a follower of Islam), and a Jew was probably written in Amsterdam by a Sephardic Jew. The four dialoguers discuss the merits of their varied faiths until ultimately the Jew is shown to follow the true faith.

The Amsterdam communities, made up of Sephardim and Ashkenazim, were significantly impacted by the rise of the false Messiah Sabbetai Tsevi – to the point that non-Jewish works were published to describe the incredible movement that had arisen around this charismatic figure. His conversion to Islam in 1666 did not stop the Sabbatean movement, which persisted long after his death as well. When Nehemia Hiya Hayon came to Amsterdam in 1713 with his Sabbatean works there was an enormous controversy around him that inflamed Ashkenazim (most of whom, led by Tsevi Hirsch Ashkenazi, opposed him) and Sephardim – notably David Nieto, Moshe Hagiz, and Joseph Ergas – who wrote and printed a number of tracts against Nehemia Hiyya Hayun. These four, in both Hebrew and in Spanish, in manuscript and in print, are all bound together in a single volume at Columbia, presumably for use by someone very interested in the case, possibly as it was unfolding.

This is only a sampling of the extensive collections at Columbia Libraries relating to the Sephardic Jewish community in Amsterdam. We continue to collect manuscripts about the Jews in Amsterdam, and a recent acquisition of letters from the early days of the Sephardic community there is now digitized and available here.