In the first hundred years of Jews at Columbia we already saw how Columbia – as an institution in the middle of a major city (unlike its Ivy-draped peers) – took a bit of a different turn when it came to inclusion of people who practiced religion differently than the majority. This second post in the series will show just how different an institution like this could be. This is not to say that there was no discrimination – but Columbia’s relative openness to Jews also gave it the honor of being the first in many areas (although, perhaps, the bar was not very high).

In 1859, the Survey of Public Libraries showed that Columbia’s collection of Hebrew books was in the top five in the country, with about 100 volumes. This was not terribly surprising, considering the Columbia was built on a strong foundation of Hebrew scholarship. Incidentally, Union Theological Seminary, whose Burke library would be incorporated into Columbia’s Library system in 2004, had the highest number: 250 Hebrew books.

As time went on and more Jews came to Columbia, though, there were some bumps in the road. In 1865, a Jewish student was refused to be excused from church services (mandated for all students). The request was written by Dr. Adler, a rabbi at Temple Emanu-el in New York, asking for his son to be excused on account of his son “being destined for the Jewish ministry.” While that request was refused, documents in Felix Adler’s files in the archives show that there was at least one time where he was allowed to retake an exam that he missed on a Saturday “due to religious scruples” (i.e. the observance of Shabbat). Dr. Adler had two sons who went to Columbia, Felix, ‘CC 1868, and Isaac, ‘CC 1870. It is likely that Felix was the one destined for the ministry, as Isaac became a doctor, while Felix taught “Hebrew and Oriental Literature” at Cornell in 1874, before coming back to Columbia to teach Social and Political Ethics in 1902. Felix Adler is famous for founding the Ethical Culture Movement (it seems that he did not actually follow his father’s wishes for his “destiny”).

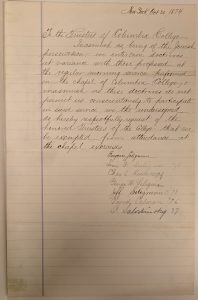

In 1874, seven students – Eugene Seligman, Louis F. Seligman, ’77, Chas S. Rudakopf, George W. Seligman, Jeff Seligman, ’78, David Calman, ’76 I. Saloshinsky, ’77 – wrote a letter requesting to be excused from church services. These students were denied as well.

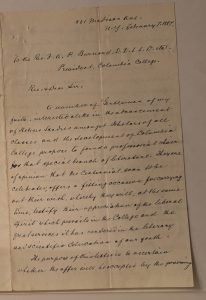

Notwithstanding this, within 15 years there would be remarkable changes coming – not just for Jews, but for Jewish education at Columbia. On February 7, 1887, Gustav Gottheil, another rabbi at Congregation Temple Emanu-el, sent a letter to Columbia President F.A.P. Barnard. The letter began: “A number of Gentlemen of my faith, interested alike in the advancement of Hebrew Studies amongst Scholars of all classes and the development of Columbia College propose to found a professorial chair for that special branch of literature.” The topics of instruction, though were to be much broader than one might think for a professorship in “literature”:

The subjects taught shall comprise; The Aramaic versions of the Scriptures, the Mishnah, the Talmud, the history of Jewish Exegesis and Hebrew Grammar, post-biblical Poetry and Philosophy and the Secular history of the Jews since their final dispersion.

In looking at the subjects, it is fascinating to think that nearly all of these areas are now taught at Columbia – but by multiple professors, not just one, and with an entire Institute built around the subject! But that is a story for a later post.

The purpose of the letter was to gauge the interest in such an offer at Columbia. It continued: “The professorship is to be placed on the identical footing with all others in the College, subject to the same Laws and Regulations and Enjoying the same privileges.” Throughout the letter, Gottheil emphasized that the subject should be taught in the same way as other courses, “free from all religious bias.” Gottheil suggested that the position would be for a five year term, after which the College and the donors would evaluate the position and make a decision on whether it should be continued. On May 2, 1887, the Trustees voted to approve the chair, “express(ing) with great pleasure their approval of the same.” Richard James Horatio Gottheil, son of Rabbi Gustav Gottheil (CC, ‘1881, PhD University of Leipzig 1886), would be hired to the position of “Chair of Rabbinical Literature” in 1890. By 1893, his courses taught would include Biblical Hebrew (with original texts) and Rabbinical Hebrew (via the Mishna, Sa’adya Ga’on, and Maimonides), Semitic Epigraphy, Assyrian, Arabic (including readings in the Qur’an and other texts), Syriac, and “Introduction to the Study of Language.” The name of the position would change with time (updating to include words like “Semitic” and “Oriental,” and eventually removing “Rabbinical”). Richard would remain the incumbent for over 40 years until his death. In 1950, Gerson Cohen would be appointed to the Gustav Gottheil Lecturer in Semitic Languages, which he held until 1959. Perhaps this was yet another iteration of the same chair.

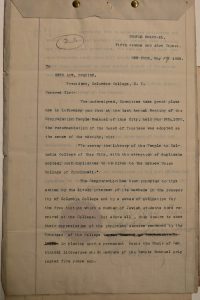

In gratitude for the university’s agreement to host the chair (and ultimately supporting it internally), Temple Emanu-el would take another step in its support for Columbia: the donation of an incredible library. Temple Emanu-el had acquired a collection of books in 1872 from the Amsterdam bookseller Frederik Muller to support its fledgling theological college (thanks to Jason Kalman for informing me about the theological college at Temple Emanu-el). The collection contained about 2500 books and 43 manuscripts, and included books from the collections of Giuseppe Almanzi of Padua, Ya’akov Emden of Altona, and S. D. Lewenstein of Suriname. In the letter from the Temple’s trustees about the collection, the reason for the gift was presented as follows: “The Congregation has been prompted to this action by the lively interest of its members in the prosperity of Columbia College and by a sense of obligation for the free tuition which a number of Jewish students have received at the College, But above all, they desire to show their appreciation of the important service rendered by the Trustees of the College in placing upon a permanent basis the Chair of Rebbinical (sic) Literature which members of the Temple Emanuel originated five years ago.” (Columbia University Trustee Minutes, June 5, 1892, p.173)

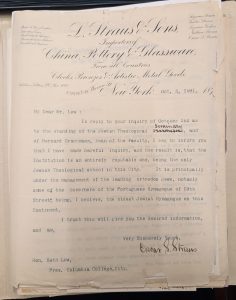

What was the free tuition offered by the college? It appears that Columbia had an agreement with multiple seminaries (including Union Theological and others) allowing free tuition to their students taking classes at Columbia. When the Jewish Theological Seminary of America was established, Columbia President Seth Low reached out to his friend (and donor of 135 Jewish manuscripts to the library,) Oscar Straus. Straus’s letter confirmed the new JTSA as a legitimate institution, and so the free tuition would be applied to students at JTSA as part of this program. This would remain in place until the statute of free tuition for seminary students from the six of the seven seminaries under the program (Union was deemed an exception for various reasons) was removed altogether in January 1925 by the Board of Trustees.

The Temple Emanu-el gift to the library would set off a series of additional gifts from its members and leaders, including Stephen S. Wise, who donated his father Aaron’s collection to the library in 1900.

In 1902 a new president would take over: Nicholas Murray Butler. Under his leadership, quite a bit would change for Jews at Columbia – in both terrible and wonderful ways.

Once again, I am deeply grateful to Records Manager Joanna Rios and University Archivist Jocelyn Wilk for assistance in gathering this information together.