Noa Tsaushu is a doctoral student of Yiddish Studies at Columbia University, currently working to complete her dissertation titled “Yiddish Art: The Desire for Cohesion among the Soviet-Yiddish Avant-Garde.” She is this year’s recipient of the Joseph Kremen Memorial Fellowship in East European Arts, Music, and Theater at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, and had recently translated and contributed to a volume of works from the Merrill C. Berman Collection titled Jewish Artists, Jewish Identity, 1917–1931. The libraries recently acquired a copy of Issachar Ryback’s Shtetl, mayn khorever heym: a gedekhenish, which is featured in Noa’s dissertation, and we are grateful for her generosity in sharing some information about this fascinating and chilling work.

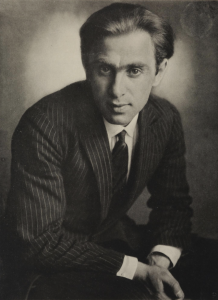

Issachar Ber Ryback (1897-1935) was born in Elisavetgrad (now Kropyvnytskiy, Ukraine). His traditional Jewish education began relatively late and was quickly replaced by art education. By the age of twelve, he had already attended painting and drawing classes and worked in monasteries across the Kherson province, painting decorations and ornaments. In 1912, at the age of fourteen, he entered the Kyiv Art School where he studied intermittently for about six years. Paintings from the period depict scenes of dancing Jews and traditional skilled workers and are indicative of Ryback’s growing interest in Jewish subject matter. Much like his contemporaries, Ryback was deeply invested in the notion of national determination and was grappling with the question: what makes art Jewish?

An expedition that Ryback took with El Lissitzky (1890-1941) through the Pale of Settlement in 1915-1916 turned to folk art to answer the question. The artists examined visual and plastic motives found in traditional architecture, decorative art, and ceremonial objects. The notes and sketches that they took while traveling synthesized past artistic production to conceptualize their own, and their later recollections provide an instructive taxonomy of Yiddish avant-garde syntax.

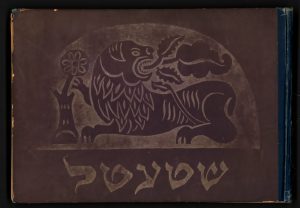

Shtetl, mayn khorever heym: a gedekhenish [Shtetl, My Destroyed Home: A Recollection] is a quintessential example of this syntax. The lithographic album was published in Berlin of 1923 (Farlag Shveln), seven years after the expedition. As history unfolded, the Russian empire collapsed and gave rise to the Soviet Union, with revolution, civil war, and pogroms that rapidly ensued. Entire communities perished, hundreds of thousands of people were killed, millions were displaced, and the Jewish artistic wealth that had so fascinated Ryback was on the brink of extinction.

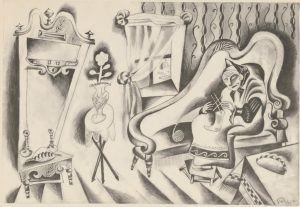

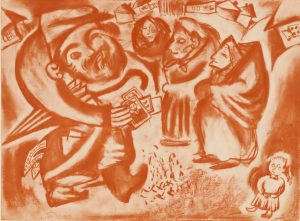

Ominous dark tones, oblique angles, and contorted proportions dominate Shtetl, and depict everyday scenes of traditional Jewish life, a subject matter that had been mutilated beyond recognition. Ryback’s response to the calamity reflects a marginalized Jewish anxiety. Unlike the Cubists whose grand gesture disintegrated the object in its entirety, Ryback chose to keep his objects intact and distorted their spatial coordinates to the highest point of tension. The manipulation results in oblique objects and underscores the material destruction of his native landscape.

Ryback’s oblique objects are ethnographic artifacts, manipulated to emphasize the formal idiosyncrasies of Jewish history. He arranges them in compositions that articulate a syntax of perpetrator and victim and prioritizes the mimetic gesture to relational violence. Through formal manipulation Ryback synthesizes notions of visuality, palpability and plasticity into the traditional domain of Jewish culture and reclaims them as Jewish art.