As part of the follow up on the fantastic work that was done by Kelilah, Hannah, and Avinoam, I have been revisiting some of the interesting materials that they came across while working on cataloging our rare Judaica imprints. Below is just a sampling of some of the wonderful materials that we have in the Rare Book and Manuscript Library:

-

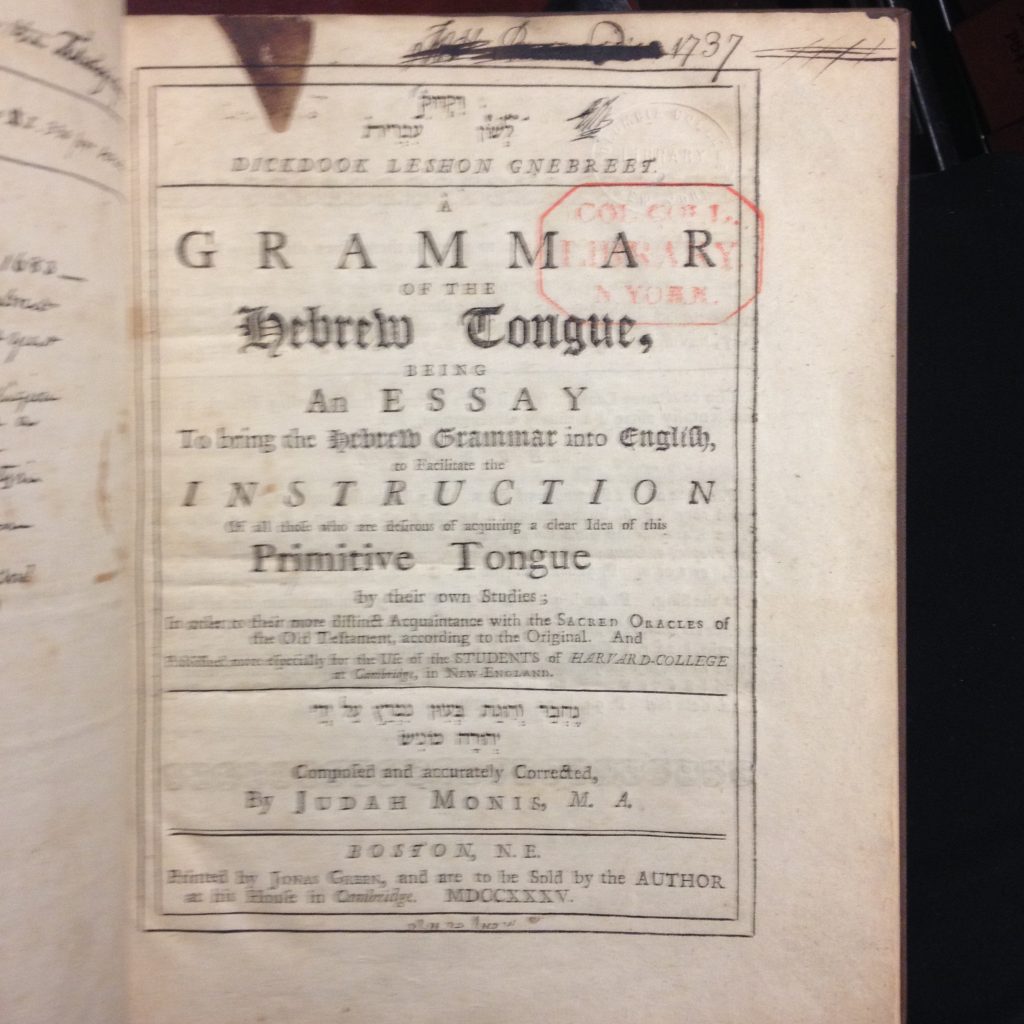

Grammar of the Hebrew Tongue (B893.14 M74)

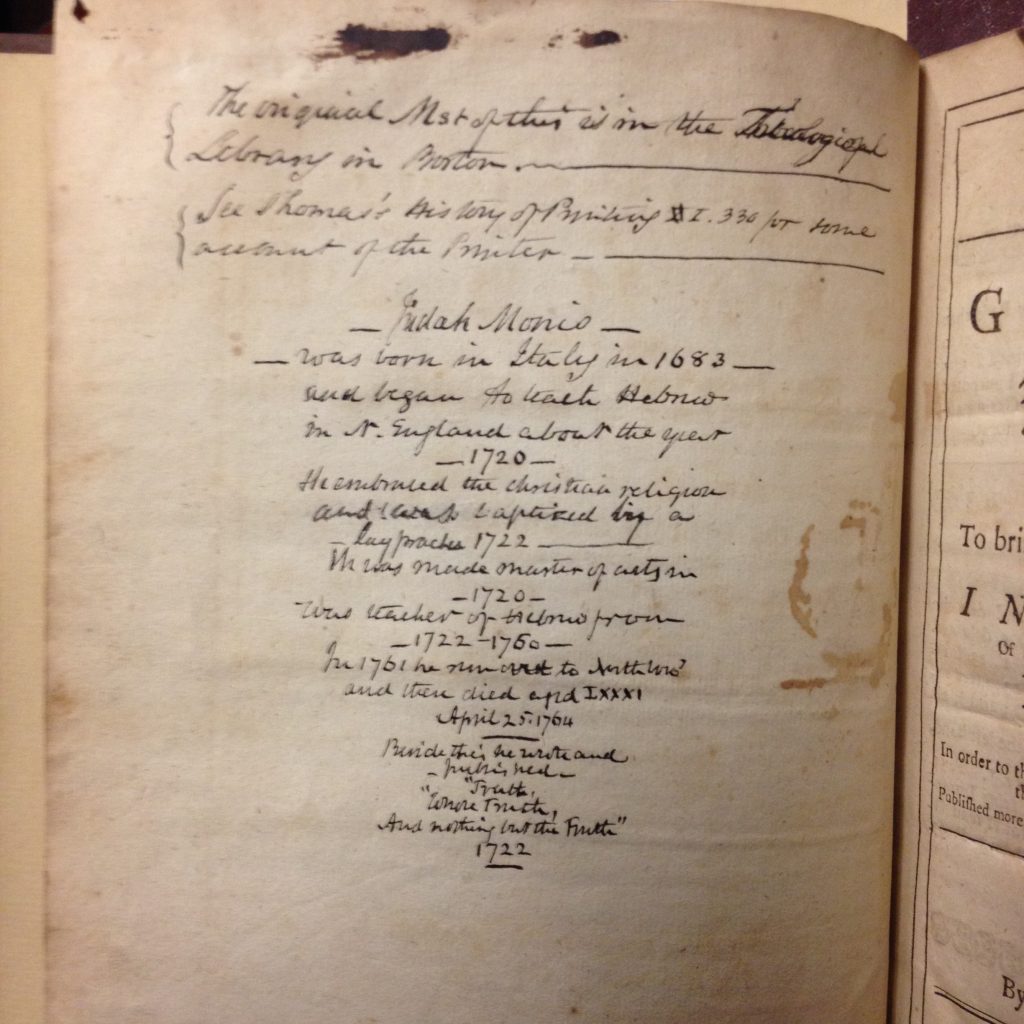

Grammar of the Hebrew Tongue (B893.14 M74) It isn’t surprising, given the strong history of Hebrew at Columbia since its inception, that wehave a copy of Judah Monis’s Grammar of the Hebrew Tongue, the first book to be printed using a significant amount of Hebrew type in the Americas. Due to lack of Hebrew type availability, Monis convinced Harvard to order the type specially from London (prior to this printing, students had to copy his textbook by hand for his class). Columbia’s copy was owned by someone (perhaps one of Monis’s students) as early as 1737 (see photo above), and there is a description of Monis and his work on the flyleaf facing the title page of the book, as pictured on the right.

-

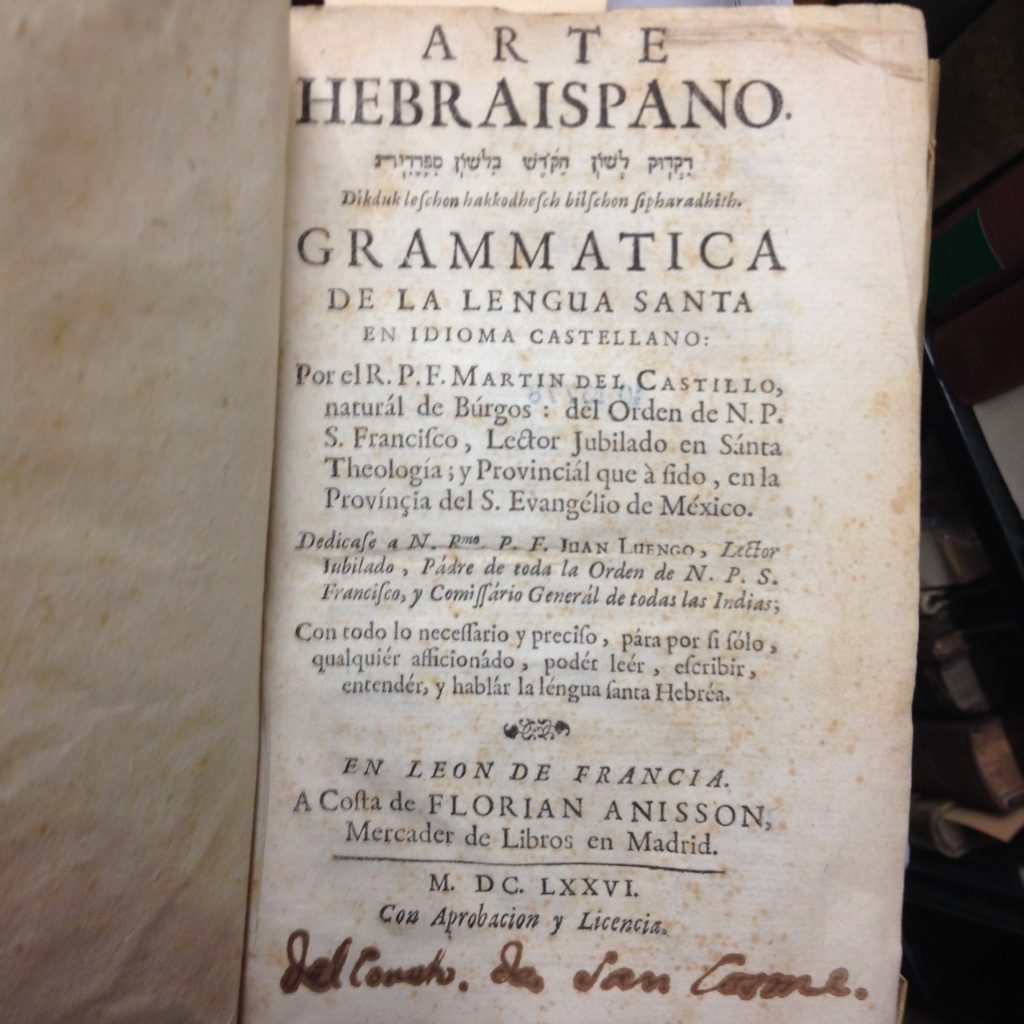

Arte Hebraispano (B893.14 C276) An earlier book with American-Hebrew connections is the Arte Hebraispano, printed in Lyon, France, in 1676.The book’s author, Martin del Castillo, was a “calificador” (an expert consultant) for the inquisition at the Monastery of San Francisco in Mexico City. Not having access to the necessary type in Mexico City, he sent his manuscript to Lyon for printing. The author includes an apology, noting that, as the book was printed so far away, there were many errors made in printing. Columbia’s copy had been previously owned by Monastery of San Cosme in Mexico City. This seems to be the oldest Hebrew grammar written (but not printed!) in the Americas. [Many thanks to Dr. Francois Soyer, who explained to me the difference between an Inquisitor and a calificador. Thanks to Dr. Jesús de Prado Plumed for clarifying that this is a solely Hebrew grammar, not a Judeo-Spanish book.]

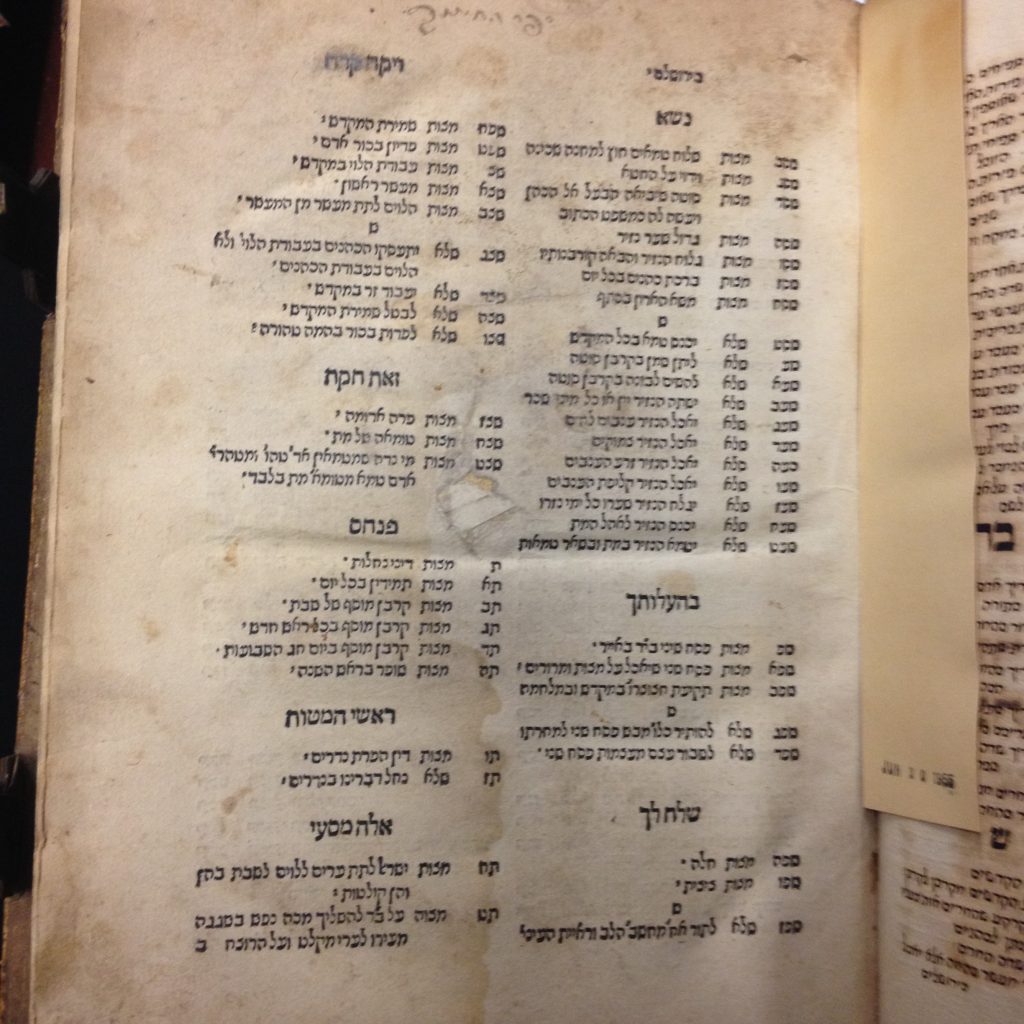

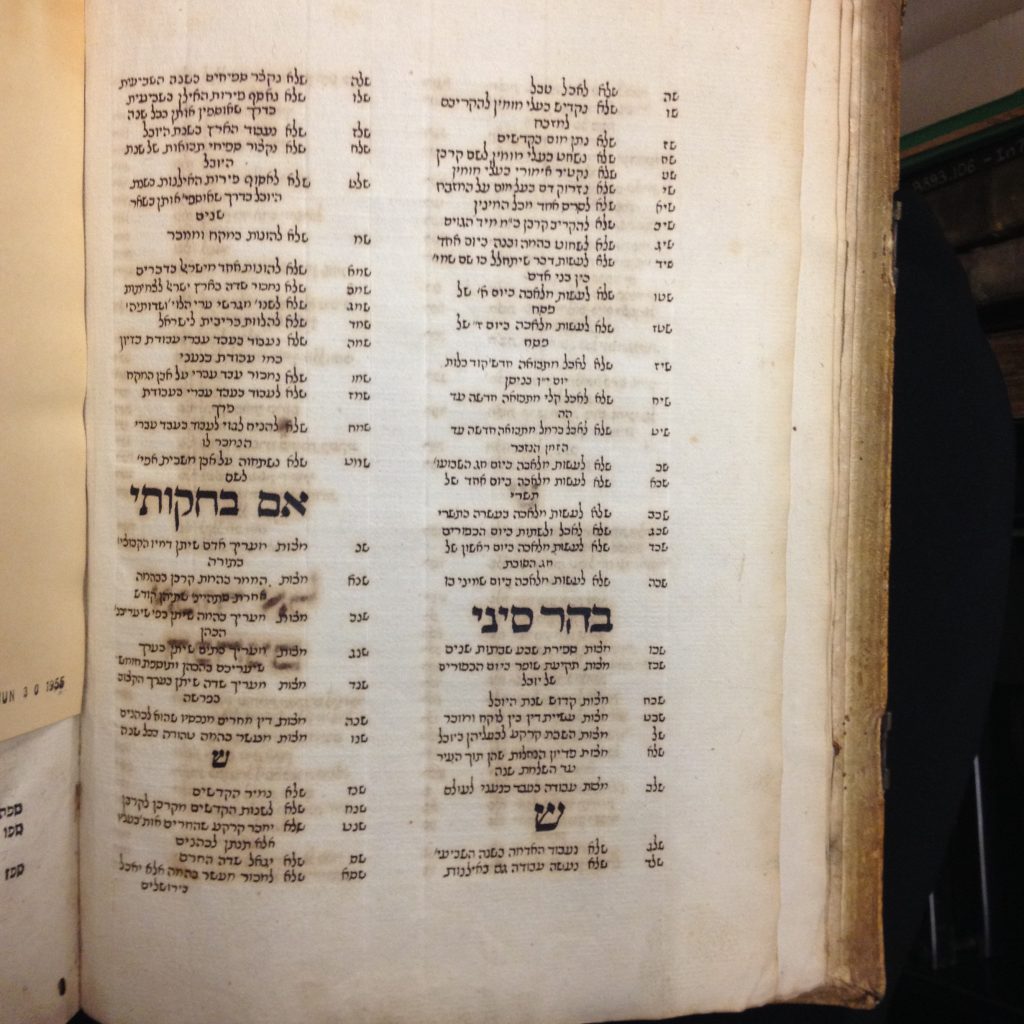

- Another book comes from a century earlier. Printed in 1523 by the famed Venetian printer Daniel Bomberg, this Sefer Ha-hinukh was missing some pages. The book’s owner painstakingly copied the Hebrew type to fill in the missing leaves. Can you tell which was printed and which was handwritten?

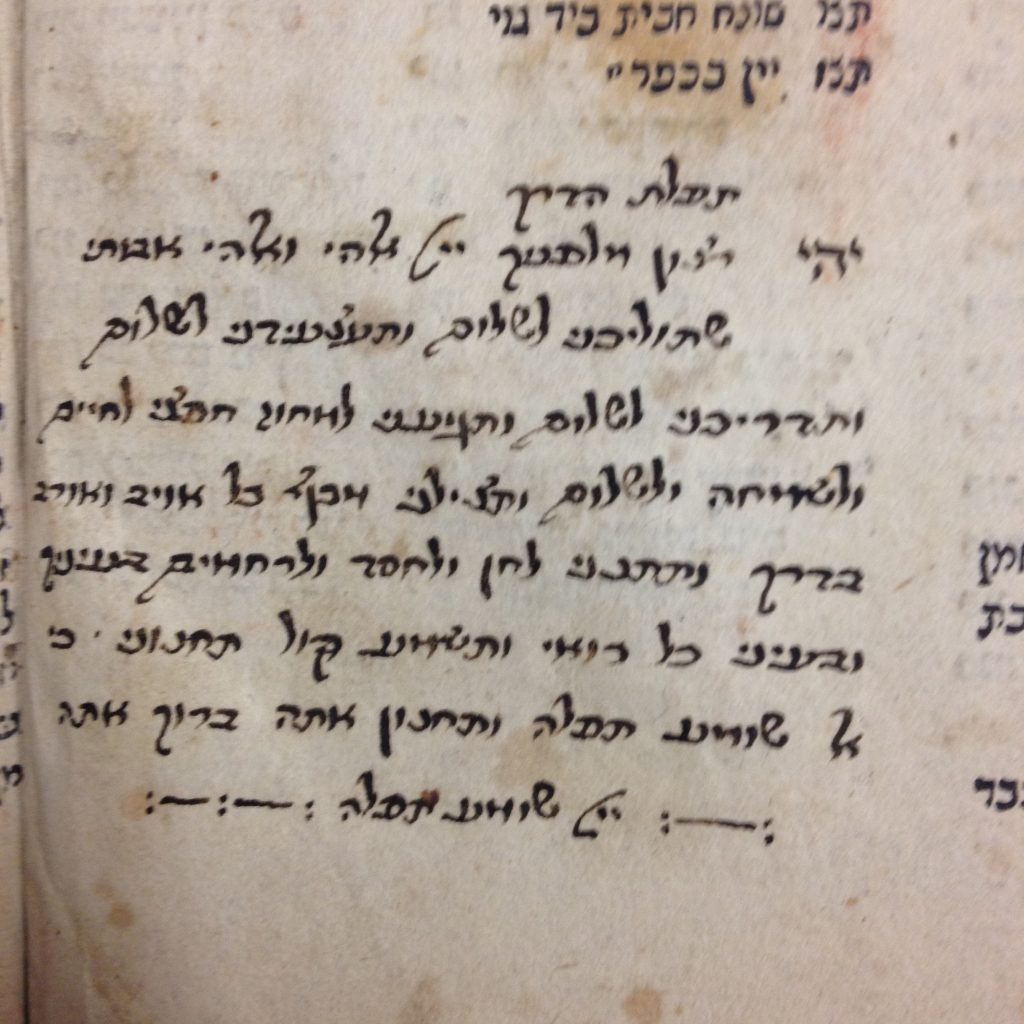

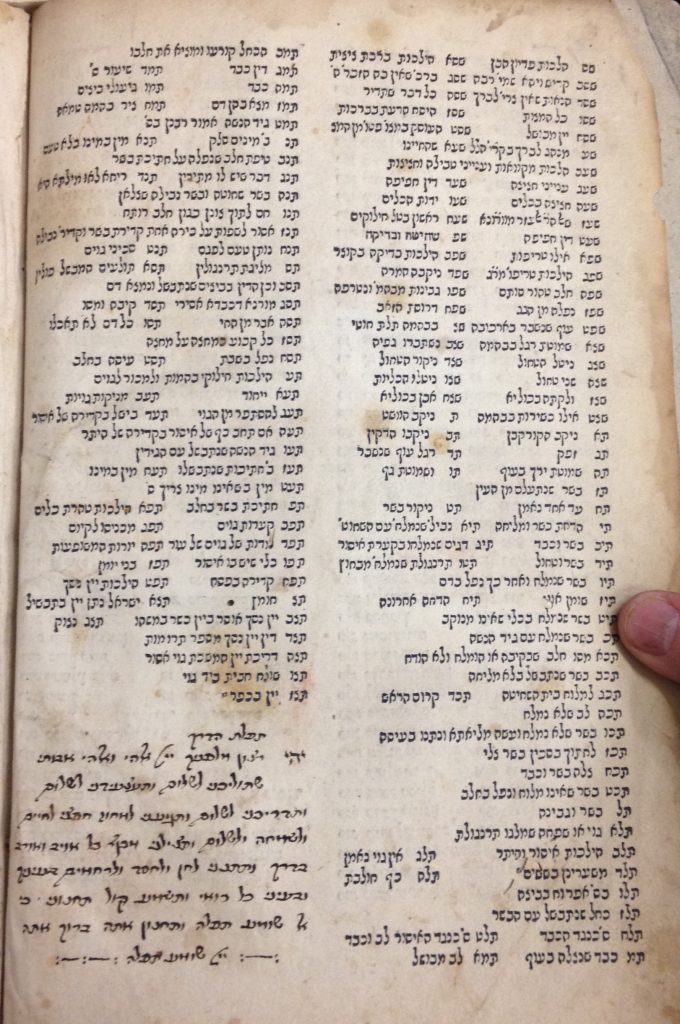

Sefer ha-hinukh (B893.1NL Aa75) - Jews traveled for many reasons: persecution, trade, marriage, to name just a few. The owner of this Sefer ha-Rokeah (an ethical work, this one printed in 1505) apparently traveled often, but wanted to bring his book of ethics along on his journey. At the end of the front matter, right before the text begins, the owner wrote Tefilat Ha-derekh, the Wayfarer’s prayer, as shown below.

Sefer ha-Roke’ah (B893.1 J881) -

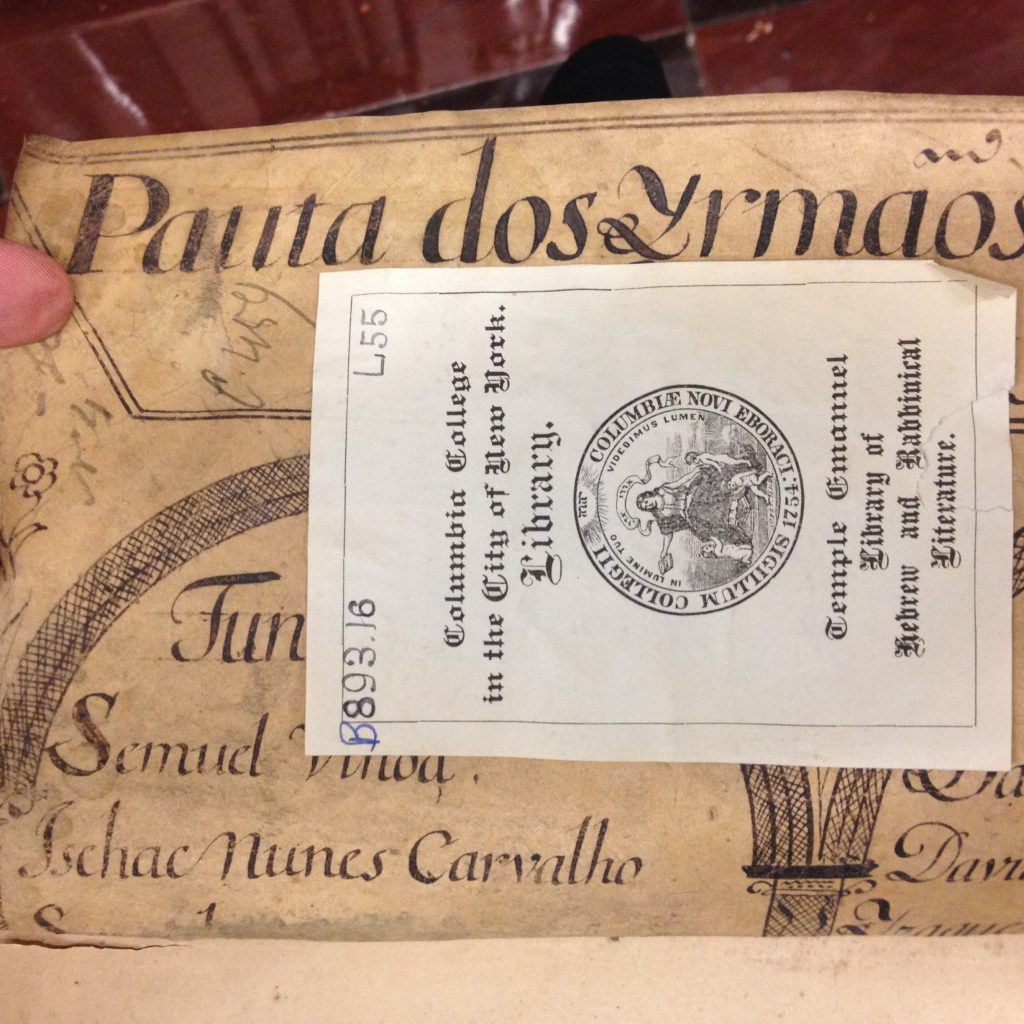

Nefesh ha-hokhma (B893.16 L55) We know from owners’ marks that the kabbalistic text, Ṿe-zot ha-sefer ha-Nefesh ha-ḥakhamah was owned by Ya’akov Yisrael Levenshtat.

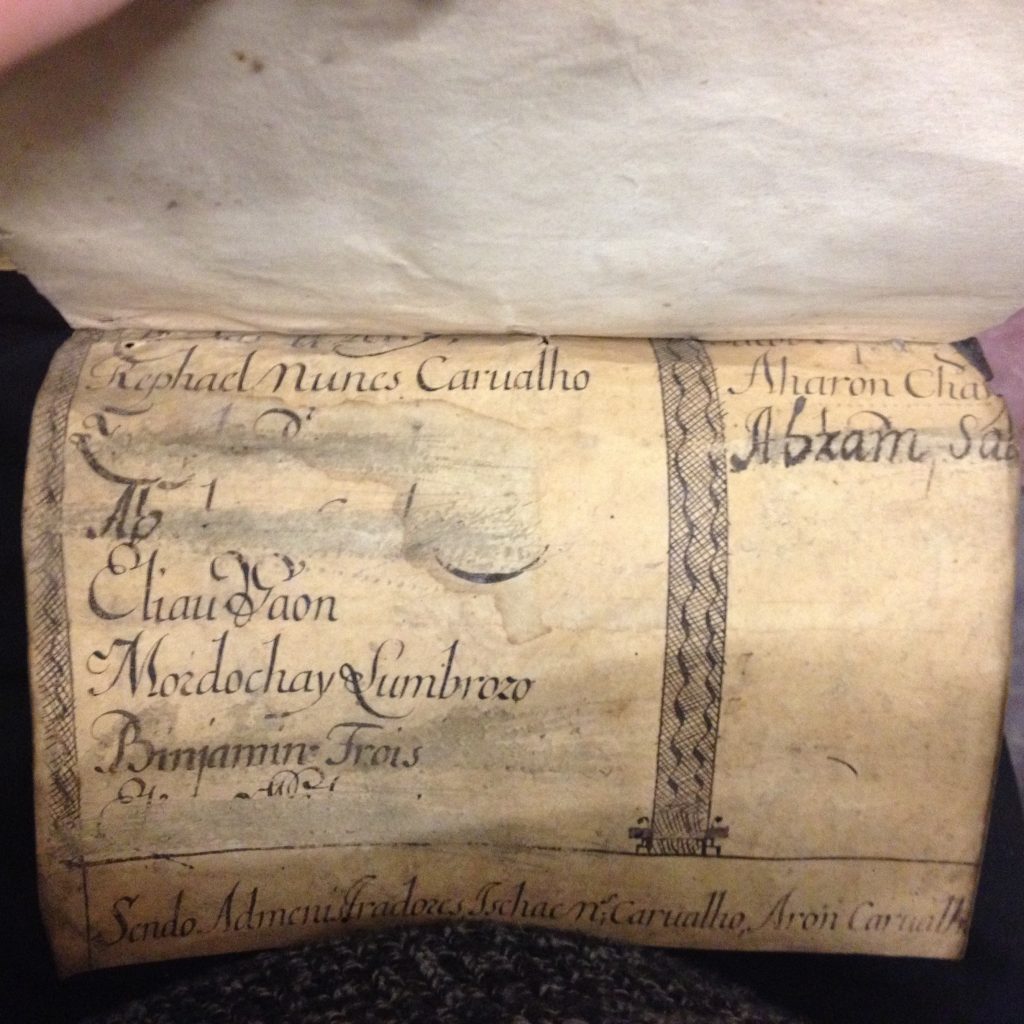

Nefesh ha-hokhma (B893.16 L55) Not much is known about Levenshtat himself, although about 85 of his books were included in the collection donated to Columbia by Temple Emanue-l in 1892. This book was bound in a piece of parchment that included a list of names. The front board (partially obscured by the bookplate given by Columbia to the Temple Emanu-el books) was the top of the document, reading (in Portuguese), Pauta dos Yrmãos, or List of Brothers. It is a list of the founders of a “pious organization” from late 17th century Amsterdam. Some of the names mentioned include:

- Ischac Nunes Carvalho

- Rephael Nunes Carvalho

- Eliau Gaon

- Mordochay Lumbrozo

[Many thanks to Dr. Aron Sterk for his assistance with identifying this document.]

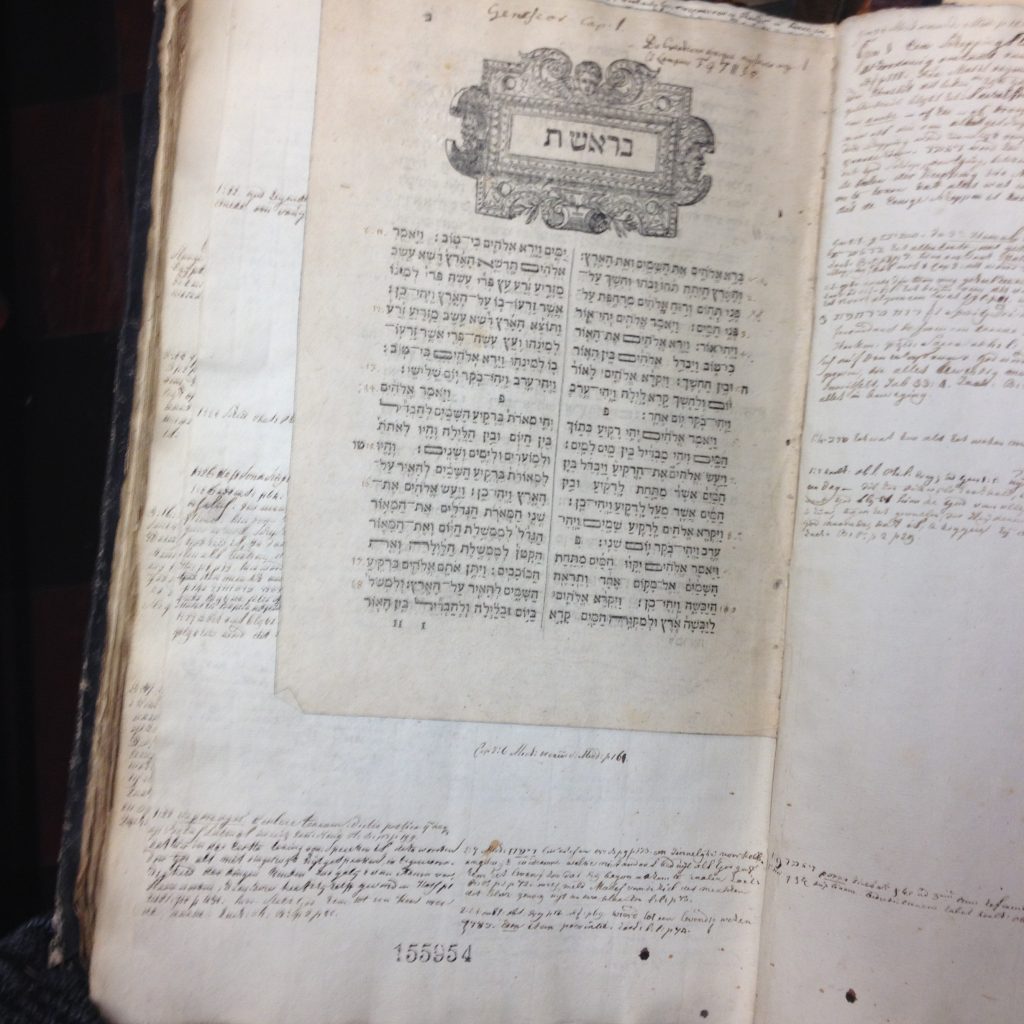

- The last item, a Hebrew Bible, was probably owned by a Christian interested in studying the text in its original language.

The owner had a special binding made for the book to allow for his study. Between each leaf of the original book, the binder inserted a much larger paper for comments and notes. This way, the owner could add his extensive glosses to the text without interfering with the original. The binding nearly doubled the size of the book, as shown here.

The owner had a special binding made for the book to allow for his study. Between each leaf of the original book, the binder inserted a much larger paper for comments and notes. This way, the owner could add his extensive glosses to the text without interfering with the original. The binding nearly doubled the size of the book, as shown here.