Day 1: I gingerly wriggle the lid from the first of a dozen record cartons in the Alison Cheek Papers; greeted by a slathering of manila and jewel toned folders that hug swatches of lined paper, printed printed paper, heavy stock paper. Handfuls of leatherbound materials peek from the depths of the cardboard box. Tenderly, I relieve a single piece of paper from the taught family of folders. I cannot recollect what was written on this inaugural sheet, but I remember the feeling of awe. A whole fleet of diaries detailing every appointment from 1983 – 2005. Handwritten student notes on softening paper – beveled edged and turquoise blue lines preserved. Everything must be essential, treated with veneration; contents adoringly removed from their containers one precious item at a time. The archival manual estimates that the initial survey for each box should take roughly fifteen to twenty minutes. This first box entrances me for nearly an hour. I proceed this way – setting timers that I foolishly think my formidable will can heed. Smiling nostalgically, my supervisor regails me with the memory of her first archival box, knowing full well that my glacial pace will soon quicken and my non-discriminatory reverence will wisen into discernment.

Week 2: Upon completing a day’s work in a week, I begin processing the first of the five series: Correspondences. So many letters. How precious to behold these artifacts of relationships. Wrestling each letter from its envelope with surgical precision, I delicately layer the two; fastening each couple with a neon archival clip. With each repeated movement, the different types of correspondence begin to form a haptic predictability; the heft of an envelope indicates a certain institution, the fluttering of thin blue on the pads of my fingers means I am holding letters sent between Alison and her parents.

Month 2: Although my pace only ever develops into a foal’s gait and never a horse’s gallop, I resist the urge to read everything I touch, until touch itself begins to guide me. Here, the archive teaches me the dependability of my senses. My eyes become trained in recognizing patterns: Alison’s writing, the location of dates on sermons. Names even leap from piles of paperwork, and glossy prints make themselves known as junk mail. Even without glancing, I know by touch that the thick stock paper in my palms is a handwritten sermon. I smell old newspapers, feel congealed eraser shavings brushed up against my hand, hear the buckling of overstuffed folders.

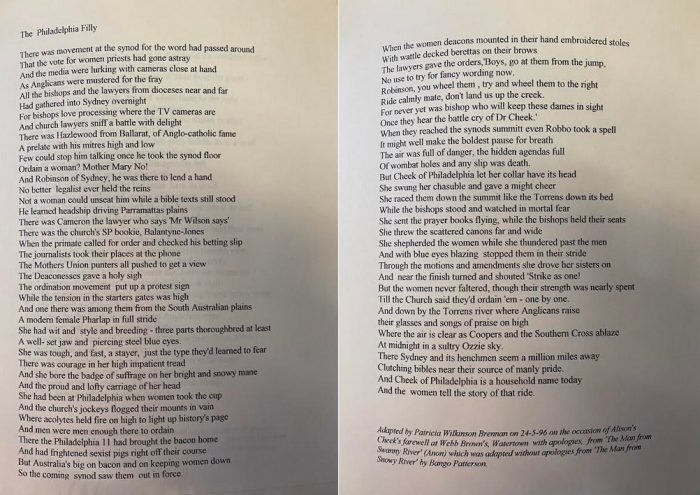

To learn through the senses about someone’s life is a type of inheritance. As a scholar, I read hundreds of pages a week, learning only what the author and editor allow. But as an archivist, I compile a lifetime into boxes, learning the potential significance of a sermon by how many times its author printed it. Though interpreting an item’s value on the basis of its recurrence is a case study in correlation-equals-causation (which we know to be false), I begin to identify the thematics of Alison’s preservation. Whether that preservation reflects deliberation or ambivalence, the sheer materiality of Alison’s records imposes a physical presence that requests the attention of my senses.

Month 3: In ten boxes, I impose order on the artifacts belonging to someone known for her religious disorder. One of the first eleven women ordained into the Episocopal priesthood in 1974, Alison’s lifetime of devotion and defiance is not just organized neatly into ten boxes. Her lifetime is materialized in the addresses she penned, in the photographs she touched. After the winter thaws and the floors have been swept, the archival doors swing open to the spring and bellow out for guests. To archive is not simply to structure, or excavate value, or even to hold every item with reverence. To archive is to prepare material inheritance and welcome everyone to the table. -LN