Credit to: MRL1: German Missionaries in Cameroon Reports, The Burke Library Archives (Columbia University Libraries) at Union Theological Seminary, New York.

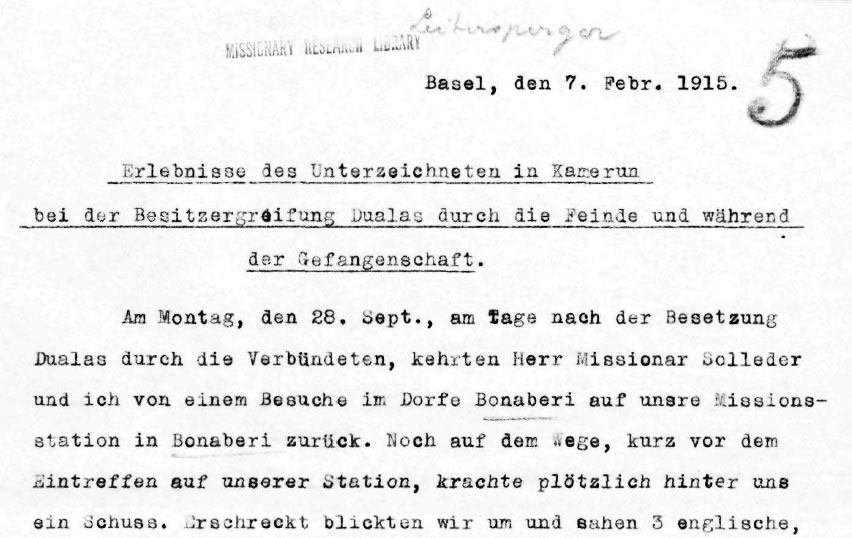

One of the great benefits of interning at the Burke Library Archives last spring was the opportunity to fuse several of my skills in the various projects I undertook. One of these projects was translating the reports of German-speaking missionaries to Cameroon who were taken prisoner in the fall of 1914 when the English and French armies captured Cameroon’s capital, Douala, and the surrounding areas. These fascinating reports tell of injustices done to the missionaries while simultaneously revealing layers of racism, prejudice, nationalism, and self-righteousness festering just under the surface of their statements. Written just weeks after the missionaries’ return to their homes in Germany and Switzerland in early 1915, the sentiments are raw, the emotions strong, and the wounds still fresh.

The thirteen reports are written as first-person chronological narratives of each missionary’s personal experience as a prisoner of war. All of the missionaries were members of the Basel Mission and most were stationed in Douala. Reading the reports one after the other is like watching a film of the same event made from thirteen different perspectives. From the individual voices, some harsher and some more reserved, an overall impression of the everyday injustices and terrors of war emerges.

In almost every report, missionaries are stripped of their belongings, their homes ransacked and their gardens robbed and trampled. Conditions for sleeping and washing in the various make-shift prisons are disgusting, and the food almost inedible.

All reports are written by men, most of whom also had wives whose experiences are only reported second-hand. Missionary Bührer writes: “Mrs. Gutekunst and my wife were held for hours by native soldiers who broke into and invaded our Akwa house after I left with random and repeated orders and counter orders until the six brute soldiers pilfered the property of Mrs. Gutekunst and finally left.” Exactly what Mrs. Gutekunst and Mrs. Bührer experienced in those hours remains, to a great extent, a mystery.

The reports are also filled with examples of English prejudice against the Germans they took prisoner: Missionary Hecklinger writes “The treatment on this ship on the side of the English, especially the stewards, was thoroughly ignoble. The latter said swear words like bloody swine, bloody dog, German bastard and others.” Swiss citizen Bührer reports that in response to his complaint that he was not allowed to enter his own offices at his Swiss-based mission, an English commanding officer quipped: “What, the Basel Mission neutral? Go on! You Swiss-Germans are three-fourths Germans of the Reich.”

Yet just as the missionaries complain of the discrimination they suffered, their own prejudices emerge, sometimes even against the Cameroon people they had sought to convert. Bührer writes: “Marching like prisoners next to black soldiers with bayonets propped up, we were subjected to the disdainful glances and shouts of delight in our misfortune from the Douala people loitering about.” Missionary Gutbrod is more explicit in his racism: “It is hair-raising how the English treated us in front of the natives, or how they allowed us to be treated by them. The German name has been trampled into the dust by them, and the German mission wasn’t spared. We shouldn’t be surprised then when some of the natives don’t remain true and treat Germans the way that they shouldn’t be treating them! The English are to blame, not the blacks. […] Not only Germans but the respect of the white race has suffered greatly. We’ll have to see what comes of it.”

While these jarring sentiments might lead some to lose sympathy for the missionaries, most of the experiences recounted in the reports do not allow for such clear‑cut finger-pointing. Some instead develop out of a sort of chaos of war with no particular person or group left to blame. One of the most frightening of these episodes occurs in the report from Karl Wittwer, a Swiss missionary stationed in Ndunge (also spelled Ndoungue and Ndoungé) north of Douala. Wittwer recounts how the English troops attempted to transport prisoners on a broken train car:

The next morning, we were brought back to Ndunge, from which we began the journey to the coast together with my wife, child, and the other members and guests of the station. Other prisoners joined us at the nearby railroad station in Mambellion. The women, children, and luggage were loaded onto an open freight car. Since there were no functioning locomotives on hand and the car had no breaks, long ropes were tied to the back of the car, and they had blacks hold these so that the car would not take off too fast going down steep slopes. An imprisoned rail worker who knew the stretch very well and did not completely trust this set up offered to lead the transport. He was refused. It soon became clear that there were not enough men holding the ropes. The car started to run wildly. It could have easily come off the tracks at a sharp curve. Furthermore, both the women sitting on the speeding car and we men rushing after them knew that the bridge some 30 kilometers ahead had been blown up, and if the car were not stopped, it would fly out into the Dibombe River. In their desperation, the women began to jump off one after the other. Although the first to dare to jump—an injured black soldier who had been sitting on the car—fell under the wheels and was killed instantly, the women and children miraculously made it off the car with relatively few injuries. My wife, who together with our 2 ½ year-old was the last to jump down, had it the worst of anyone. She fell on her back and apparently landed on a rock, which left her in pain and almost unable to lie down for weeks. And the back of our child’s head hit her so hard on the mouth that several of her top teeth became loose and some fell out. We will never forget this ride of terror.

Indeed, all of the missionaries’ journeys from working freely in Cameroon through the indignities of imprisonment and finally to their homes in Germany or Switzerland were rides of terror. Despite their often overt bias, these reports offer a view into the difficulties suffered by peaceful civilians during a time of war. Yet even among missionaries—those whom we might guess to be most modest in their needs, pious in their thoughts, and thankful to survive encroaching war—we find indignation, conceit, and hints of seething hatred. As documents of an historical moment and evidence of the cultural attitudes at the beginning of the First World War, this collection is a gem for historians, theologians, and pacifists, and of certain interest to many others.

The German missionaries in Cameroon reports are available to registered readers for consultation by appointment only. Please contact archives staff by phone, fax or email at archives@uts.columbia.edu.