In the Spring of 2015 Union Theological Seminary students from CH108: The History of Christianity Part 2: Introduction to Western European Church History (c.1000-c.2000) viewed manuscripts and early printed books from the rare books collections at Burke Library. Over the course of the semester they chose manuscripts or early printed books to study and wrote codicological descriptions. Excerpts from their work are recorded below – along with the opportunity to read their research in full.

Dr. Jane Huber and Russ Gasdia, Teaching Fellow

**Please note: For footnote citations and bibliography, see paper in full at the above author link.

Derrick Jordans – Multaqā al-abhur

Multaqā al-abhur, Burke Manuscripts, Arabic MS13

Click here for PDF of the complete paper

This 16th century book is 21cm in height, 10 cm wide and 2.5 cm deep. The cover of the book is made of wood covered in purple leather. On the front and back covers of the book, there are impressions in the upper and bottom corners which are characteristic of tooled and stamped letter binding. The impressions in the corners of the book were made by a method of stamping the books with irons, a technique prominent in early Islamic bookmaking. Another characteristic of tool and stamped letter binding would be the “flap” design of the cover of the book, where the flap must be lifted up so that the contents of the book can be accessed. The flap which is a part of the cover, is 4.5 cm in width from the longest point of the flap to the edge of the cover, and 3.5 cm at its shortest point to the edge of the cover. This traditional Arab style binding had Persian influence and dominated leather binding from the 16th century onward and was a method of binding similar to yet different from Ottoman style binding which used intricate European influenced floral patterns and art in the book .

Link to collection level catalog record in CLIO

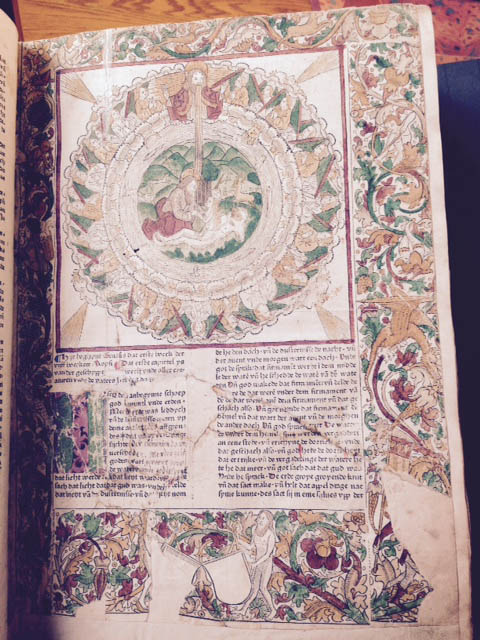

Stephanie Gannon – Bible 1478

Biblia (Low German/Niederdeutsch) : with glosses according to Nicolaus de Lyra’s postils, Heinrich Quentell, Cologne, ca. 1478, Rare Books collection/Union Rare Folio, CB80 1480

CB80 1480.

Click here for PDF of the complete paper

This bible was printed in Cologne, where Germany’s second oldest university was founded in 1388. Cologne was also the seat of the Catholic Archdiocese until 1525.[1] Nicole Howard writes in her work The Book: The Life Story of a Technology that there was a “diaspora”[2] of printers from Mainz, where printing was invented by Gutenberg. She notes that the archbishop of Mainz and his troops had sacked the city in 1462, which contributed to an unstable business climate. Printers fled the city looking for business opportunities and a stable political environment.[3] According to Howard, Cologne was their first destination. The university provided them with a clear market for their books.

Although this bible lacks a colophon, or a label at the back of the earliest books identifying the printer and place of publication, the Burke Library record designates Heinrich Quentell as the publisher. However, different sources I consulted contend that Bartholomaeus von Unckel was the publisher of the two large Cologne bibles, one of which was in the Lower Saxon dialect, the other in the West Low German dialect. While von Unckel was in fact the publisher, the financing and the printing were likely in the hands of a consortium, whose main financial backer was Johann Helman, the master of the mint for the Kaiser and a Cologne-based notary.[4] Ferdinand Geldner argues that since it’s unlikely that Unckel owned his own printing press, he probably worked with Heinrich Quentell, who was just starting out in the business at the time, to bring out these editions. [5] Indeed, editor Christoph Reske verifies this fact in his excellent reference guide on early German publishing. Quentell was active as a publisher from 1478-1501 and founded one of the most important publishing dynasties of Cologne, printing, among other things, theological and liturgical texts as well as works for university lectures.[6] It is fascinating to think that one of Quentell’s very first projects was such an ambitious undertaking. For various reasons, these two editions of the Bible must have been expensive and technically challenging.

Link to catalog record in CLIO

Emily Hamilton – 1523 Luther New Testament

Ihesus, Das New Testament teütsch, Johann Schott Strassburg, 1523; Rare Books collection/Union Rare Folio.

Click here for a PDF of the complete paper

This copy is missing the title page but includes interesting printing elements that begin after that first page. As early as the third page we can see where the ink from the first woodcut has stained the page facing it, a detail found near other heavily inked texts, as well. We know demand for Luther’s New Testament was high enough to warrant multiple printings in this second year alone; perhaps it was high enough to warrant gathering the pages for sale or binding before they had completely dried! In the listing of the books of the New Testament, as Edwards points out, Luther changes the format for those books which fall outside of his “canon within the canon” – that is, books he finds objectionable and less important than the others – separately from the others, and fails to assign the names in their titles the prefix of “Sanct” given to the others. So, where we read “Sanct Matthes” in the beginning, we only read “Jacobus” in the latter section. Some of Luther’s other opinions about the text that can be seen in his printed translation of the New Testament are found in the commentary. As previously noted, this copy kept Luther’s commentary in the margins where it was originally placed. Even a non-German speaker can see where Luther engaged the text the most by his rate of glossing, found most frequently in Romans at a rate of 2.5 glosses per page, most of which were on Luther’s essential themes of law and gospel (Edwards 117)! Given Romans’ status as one of the greatest influences on Luther as well as the location of much of Luther’s arguments for his own theological work, it is no surprise to see a long preface here as well.

This section is where readers have left the strongest record of their engagement with the text. At least two if not three different sets of handwriting and ink are found in this section and there is marginalia in the form of hands pointing to texts (manipula), illustrations, written notes, and possibly other notations. There is more marginalia scattered throughout the volume, but no one book with as high a proportion as this one. It is clear that whatever other reasons the owners and readers may have had for purchasing and making use of this book, their engagement with this particular book was as heavily emphasized as Luther’s own. It is likely that this engagement is precisely because of the references that Luther made along the margins to guide reading, though certainly it is also possible that the reader had previously read the text in Latin or even in Greek and was agreeing or arguing with changes that Luther made in his translation. Their personalities even shine through: one particularly fastidious writer has drawn many hands pointing their index finger at the text to pay attention to and has carefully each their own individualized cuff, while another writer has more sloppily drawn illustrations like faces in letters that are accompanied by large ink stains.

Link to catalog record in CLIO

Hunter Beezely – Gospel Book

[Gospels] : [manuscript], ca. 1340; Manuscripts collection, UTS Ms. 69

Click here for PDF of the complete paper

This book is believed to have originated at the Iveron monastery in Mount Athos, Greece. On January 15, 1942, Union Theological Seminary (henceforth referred to as UTS) purchased this manuscript from Vassilios Iatropoulos of Denver, Colorado, and New York City. This document is believed to have been originally purchased by Iatropoulos within Moscow, however this is largely uncertain. This manuscript is dated approximately to the 14th Century.

At some point this text found its way from Constantinople to the Iveron monastery in Greece. Established some time in between 980-983, the monastery became an influential site for the Greek Eastern Orthodox tradition. This monastery prides itself on its large library of more than 2,000 manuscripts, 15 liturgical scrolls, and 20,000 books in Gregorian, Greek, Hebrew, and Latin as well as its extensive collection of religious relics.

The manuscript is a bound collection of texts, written in Greek, with few Greek annotations likely written by a scribe or later reader. The texts included are as follows: (1) Preface to the Gospels, (2) Preface to the Lectionary of the Gospels, (3) The Gospel of Matthew, (4) The Chapter Titles to the Gospel of Mark, (5) Preface to the Gospel of Mark, (6) The Gospel of Mark, (7) The Gospel of Luke, (8) Chapter Titles to The Gospel of John, and (9) The Gospel of John. The scribe to these texts is Hieromonk Gennadios of the Hodegon Monastery and the script used is Vertical calligraphic minuscule. The ornamental decorations within the heading to each section of texts is believed to have been done by Gennadios (though this is largely uncertain).

Link to catalog record in CLIO

Kaitlyn Butler and Stuart Kay– Qur’an commentaries

Majmū at al-tafāsīr, Burke Manuscripts, Arabic MS 7

Click here for PDF of the complete paper

Though it was cataloged as a Qur’an manuscript in the original 1980’s Byrnes catalog of the Burke Library, Arabic MS7 is actually a Qur’an commentary. This is readily evident when the Arabic MS7 manuscript is compared to other Qur’ans produced in similar eras like the Burke’ Library’s MS 4. Like the Arabic MS7 commentary, this Qur’an is also believed to have been produced during the Ottoman era. The book is distinct in its consistency of format. The handwriting is consistent throughout the entirety of the text and likely written by the same scribe. The text is further evenly situated within the margins of the pages indicating the care and craftsmanship that went into its drafting. The size of the font in the Qu’ran is also slightly larger making it easier to read for various purposes.

Given the presence of the term “waqf” on the inside cover, the original owner dedicated the manuscript to an Islamic endowment following his/her death. “Waqf” refers to a compulsory donation of a portion of an individual’s wealth to a religious institution. Written in English on the inside cover, the text is labeled, “Qur’an Commandments for Islam,” which is theoretically the title of the commentary. Further, the manuscript is likely of Ottoman origin given the style of binding and the cover art. The outside cover is made of wood though it is wrapped in a decorative paper. The marbled design on the decorative paper is likely characteristic of its Ottoman origins. The text, however, is also unique in that, unlike manuscripts of a similar era, the binding and pages are cropped to be of even dimensions (7.8” and 5.5”).

Speculation that the text is of Ottoman origin is further supported given the presence of the word “teke.” The manuscript was likely given by the original owner to a Sufi monastery to which the term refers. The term itself, as compared to other terms for similar Islamic monastic institutions, was first used in the Ottomon Turkish context and may be idiosyncratic to it. Teke derives from the term taqiyya, an important concept in Twelver Shiism. The term “teke” therefore may indicates that it was donated to a Sufi dervish monastery. The term began to take precedence over the more common term “zawiya” in Turkey around the 10th/16th centuries when it began to refer more specifically to an Ottomon network of brotherhoods, more stable and permanent institutions, that was responsible for the needs of mystic communities and controlled by the state. Though, it is worth noting that there is currently no certainty regarding the distinction between “tekke” and other terms for Sufi monastic communities beyond this geographical and historical knowledge. The text further has an original “call number” written on the underside of book such that it could be identified if it was stacked with others when it was laid flat. This tells the modern observer how the Sufi community in which it was originally kept stored and organized their texts.